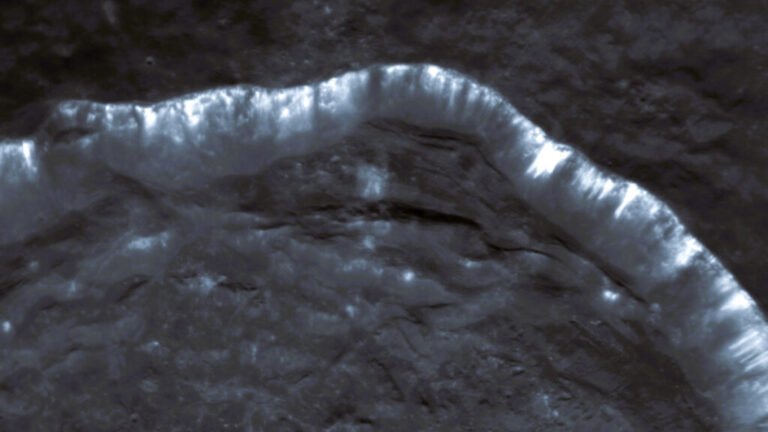

Fast ice, also called landfast sea ice, is a relatively short-lived ice that forms from frozen seawater and attaches like a “seatbelt” to larger ice sheets. It can create 50- to 200-kilometer-wide bands that last anywhere from a few weeks to a few decades and act as a site for valuable geochemical processes, breeding grounds for emperor penguins, and a protective buffer between caustic Antarctic winds and waters and inland bodies of ice.

In new research published in Nature Communications, scientists found that buried sediments can track the long-term growth of Antarctic fast ice—and that the ice’s freezing and thawing may be linked to cycles of solar activity. Given that this ice plays a significant role in protecting Antarctica’s larger ice sheets, the research could have major implications for understanding the ongoing impacts of climate change in Antarctica.

“Fast ice, especially in the summertime, is suffering the same fate as overall pack ice,” said Alex Fraser, a glaciologist at the University of Tasmania, who was not involved in the study. We’ve seen a “dramatic decrease” over the past decade, he said. “We’re down to around half of the ‘normal’ [amount].”

“To understand how humans are changing the planet, we first need to know how the planet changes on its own.”

Over the past several decades, the only way for scientists to track fast ice has been through satellite data, which can reveal the ice’s history over only the past 40 or so years. This narrow range has prohibited researchers from understanding the ice’s behavior prior to human-induced climate change.

“To understand how humans are changing the planet, we first need to know how the planet changes on its own,” said Mike Weber, a geoscientist at Universität Bonn in Germany and a coauthor of the study. The new work aimed to establish a “blueprint” for how fast ice behaves in the long term, allowing researchers to better understand how the ice contracts or expands when exposed to greenhouse gas emissions.

Sediment Secrets

To better understand fast ice history, the team turned to sediment cores from Victoria Land in eastern Antarctica. By scrutinizing laminated layers within the cores, the researchers were able to pinpoint key markers that correspond to ebbs and flows in fast ice going back 3,700 years.

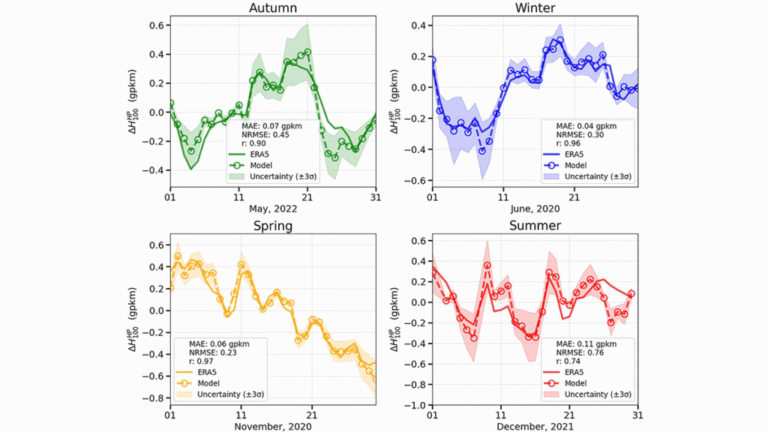

The team found that lighter sediment layers formed during summer months marked by prolonged ice loss, whereas darker layers formed during regular seasonal thawing. They also found evidence that different species of small organisms called diatoms grew during summer months versus thawing periods, further enabling the science team to distinguish the cycles. By combining these and other data unearthed from the sediments, the researchers identified recurring periods of open-water and low-ice conditions pinned to solar cycles—called the Gleissberg and Suess-de Vries solar cycles—that occur approximately every 90 and 240 years, respectively.

The link to solar cycling was surprising at first, but the researchers suggested the explanation is straightforward: Solar activity can influence winds over the Southern Ocean, transporting warm air over the Victoria Land coast and leading to ice melt.

“Laminated sediments are always intriguing because you know they’re hiding a message.”

“Laminated sediments are always intriguing because you know they’re hiding a message,” said Tesi Tommaso, a biogeochemist at the National Research Council of Italy’s Institute of Polar Sciences and lead author of the study. “When we realized that over long timescales, this laminated pattern was linked to solar activity, it actually made perfect sense—it was super exciting.”

In future work, the team plans to dig up deeper sediment cores to push fast ice records back even further. The data would be “incredibly informative,” said Tommaso.

“We have finally developed a high-resolution ‘time machine’ for a critical but poorly understood part of Antarctica,” Weber said. “It’s a testament to how interconnected our atmosphere, ocean, and ice really are.”

—Taylor Mitchell Brown (@tmitchellbrown.bsky.social), Science Writer

Citation: Brown, T. M. (2026), Sediments offer an extended history of fast ice, Eos, 107, https://doi.org/10.1029/2026EO260054. Published on 12 February 2026.

Text © 2026. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.