MUNICH — When I first saw Shu Lea Cheang’s work at the Munich International Film Festival two years ago, she buoyantly advised her audience to sneak out to the bathroom or leave the cinema if her porn-infused science-fictions’ graphic sex scenes overwhelmed (or, wink, inspired) them — a cheeky challenge very few viewers took up. I think that anecdote might just sum up the Taiwanese-American artist’s unique blend of art, tech, and porn, or her penchant for provocation.

At first glance, Cheang’s more somber science- and technology-minded survey, Shu Lea Cheang: Kiss Kiss Kill Kill at Haus der Kunst, comprising work culled from the past three decades, has little to do with her erotic fantasies, such as her film I.K.U. (2000), depicting orgasms and sperm as glossy commodities, or the lesbian sex reverie “Sex Fish” (1993). For one, there is hardly any flesh to see here. This doesn’t mean, however, that Cheang tempers her approach; the body is very much present, albeit less directly. And while the exhibition’s mise-en-scène is more spare than one would expect from her typical intense technicolor dystopias, Cheang’s febrile, fantastical narratives make this relatively compact survey feel like much more than the sum of its parts.

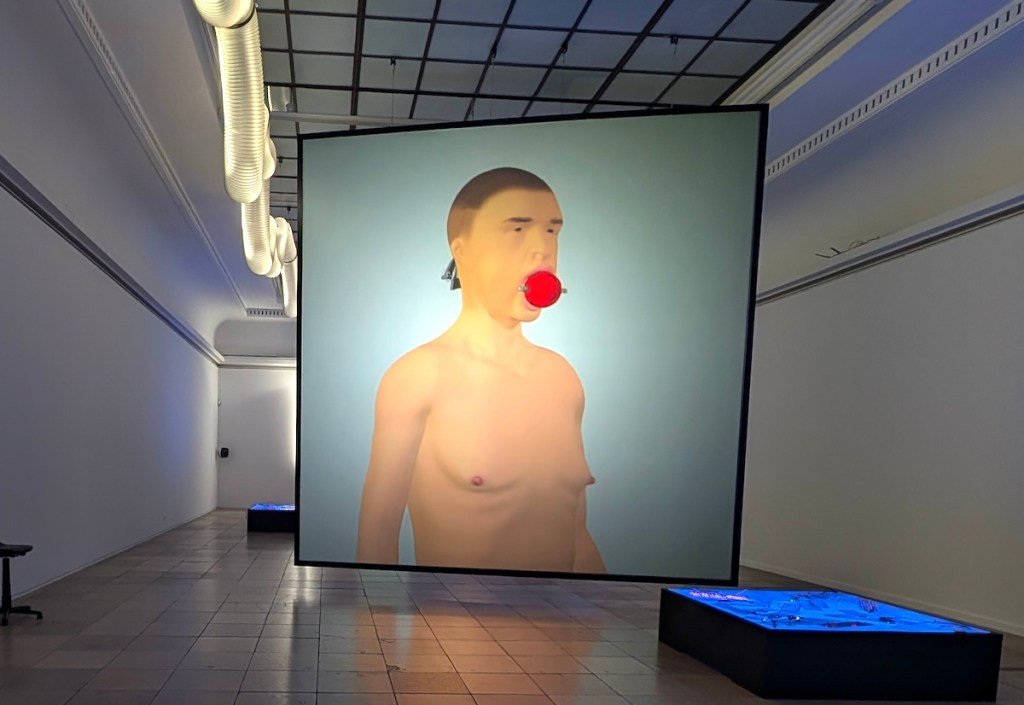

Take, for instance, Cheang’s installation “Spoken Words” (2025), which combines elements of her previous works, “Baby Work” (2012) and “Utter” (2023). From the latter, she reprises an animated avatar whose gender and race keep changing. This figure is shown on a large central screen, at first gagged, then disgorging laptop keys (some of those lie on the floor in the corner). Meanwhile, it borrows from the former work the various keyboards set on low platforms surrounding the screen. Strike the keys to hear words uttered aloud — I caught “suck,” “nipple,” “dildo,” and “mistress,” suggesting that Cheang is primarily interested in sexual language AI technologies may censor.

More broadly, one might say that Cheang is concerned with the ways technology enables not only commodification but also control of all human activity, from communication to nourishment to sex. In her installation “Home Delivery” (2025), for example — again featuring elements drawn her earlier work, in this case “Drive By Dining” (2002) — two robots move along tracks, picking up cardboard boxes, like the ones used in food deliveries, and throwing them into piles along the walls. The robots’ soundless choreography is rote and rigid; it soberly conveys the extent to which even the most primal of human needs, such as eating, now rely on technological networks. Yet “Home Delivery” takes on a different tenor once you read the exhibition text, which explains that Cheang imagines the machines as part of a post-food delivery future in which robots now aimlessly retrace their routes.

“Home Delivery” also hints at Cheang’s approach to technological waste, viewing it on the one hand as a literal, physical environment threatening to engulf the human and on the other as a renewable resource, just like organic material. This idea underpins Cheang’s last large installation at Haus der Kunst, “Portal Porting” (2025), derived from “Composting the Net” (2012) and “Portal to the Next” (2022). The former consists of multiple screens with running text sourced from internet mailing lists, which seemed to range from artist proposals to academic papers. One can pause them by striking keyboard keys. Standing in the midst of the installation feels very much like information overload, like being awash in data. Cheang, however, seems to view it more as a source to repurpose or possibly hack into. This hopeful message is embodied by the central object in the room, drawn from “Portal to the Next”: a burned-out car wreck sprouting large fungi, surrounded by large tree trunks that may have precipitated the crash, likewise blooming fungi. The work seems to suggest that information networks and data are also fungi- or spore-like: Their DNA, so to speak, contains the blueprint for suppression, but also for liberation.

Liberation might just be the central metaphor of the meditative, flowy video “Escape Artist” (2018/25). Per the curatorial text, it originates from yet another previous work, “UKI Virus Rising,” which is in turn part of Cheang’s sci-fi alt-reality project UKI (2023). In it, Reiko, a former sex worker dumped on a digital landfill, remakes herself with e-trash into a contagious virus — an image of viral mutability and generative power, particularly since Reiko ultimately rises to save the planet. At Haus der Kunst, the image of blood cells floating peacefully across a red background may not have the same explosive energy as the rebel Reiko does in the film, but it nevertheless left me thinking of the human body itself as a potent, porous, and therefore hackable system.

Shu Lea Cheang: Kiss Kiss Kill Kill continues at Haus der Kunst (Prinzregentenstraße 1, Munich, Germany) through August 8. The exhibition was curated by Sarah Johanna Theurer with Laila Wu.