I thought my days of writing about selfies were over. My book The Selfie Generation (2017) had done its job: It chronicled the form’s rise into the mainstream, from becoming Oxford Dictionaries’ “Word of the Year” in 2013 to transforming TV shows, pop psychology, marketing, and visibility for marginalized people. Today, the selfie has become so normalized that, like the texts I send and the air I breathe, I’d almost forgotten about it.

Then, the selfie resurfaced at the most basic of places — Chicago’s massive Six Flags Great America amusement park— in a most unusual way.

On a warm afternoon last autumn, my partner and I were riding the Logger’s Run, a watery roller coaster-esque ride that involves sitting in an oversized fiberglass log as it floats down a “river” — a metal slide filled with water. After many twists and turns, it ends with one big drop and a giant splash.

A few minutes later, smiling and soaked, we headed to a contraption with flying chairs. We were swinging through the air with other fairgoers when my partner discovered that her phone wasn’t in her pocket. It must have flown out during the Logger’s Run, so we raced back to it. We cut the line, weaving our way through sweaty bodies until we reached the log-dismounting area. After about 20 minutes of asking around, a guy wearing a soaking-wet blue shirt hopped out of his log clutching my partner’s iPhone. Moments later, it was back in her hands.

Later that day, as we swiped through the cute photos we’d shot on her phone, a selfie of a random man popped up. He looked like he was high above the ground. We looked at each other, suddenly very confused. Was this some sort of elaborate phone hack? Had her phone started picking up someone else’s iCloud stream? Could it be that this wasn’t even her phone?

Then it hit me: This was the same guy who had returned her phone at the log ride. For some reason, he decided to snap a selfie before the big splash.

His selfie is still in her camera roll, an odd artifact of our interaction with this stranger who found a phone and decided to take a photo. Was he bored? Curious? Hoping someone else would see it and remember him?

After much contemplation, I concluded that he likely took the selfie because he thought it would be funny. If he’d taken it with his own phone and posted it to his socials, maybe he feared it would come off as attention-seeking. Or perhaps his friends would’ve been pleased that he was having fun at Great America, and happily liked it. A selfie gains meaning based on its context, which is determined by where it’s posted and who sees it. I began to wonder why people take selfies and what they signify.

That curiosity stemmed from The Selfie Column, which I wrote for Hyperallergic from 2013 to 2014. Most people don’t wonder why someone took a selfie and posted it — instead, they assume they know that person’s intentions, turning the selfie into a projection of their own ideas. As Agatha Christie wrote in her 1930 novel The Mysterious Mr. Quin, “Nobody knows what another person is thinking. They may imagine they do, but they are nearly always wrong.” There is more to the selfie than meets the eye.

In the decade or so since its rise in popularity, the essential purpose and meaning of a selfie largely remain the same. Most of the selfies that make headlines are still accidental, or at least coincidental; a search for “selfie” brings up daredevil selfies, death by selfie, self-promotion, loneliness. What has changed is where and when people snap selfies, and the technology they use to take them.

A Brief History of the Photographic Selfie

One of the first selfies was an 1839 daguerreotype self-portrait by photographer Robert Cornelius, but it wasn’t until 1963 that artist Andy Warhol began taking selfies in photo booths as part of his creative practice. He was obsessed with documenting his existence. “A picture means I know where I was every minute,” he once said. “That’s why I take pictures. It’s a visual diary.”

Little did he know that one day, this visual diary would be public and online, for friends and strangers alike to see, depending on privacy settings. Everyone could have their 15 minutes of fame.

In the early 2010s, Kim Kardashian pioneered the selfie as it is understood today: a self-image with an awareness of potential publicity. “I can look at any photo of myself and can tell who did my hair and makeup, where I was and who I was with,” she writes in her 2015 book Selfish.

It’s easy to assume that only self-involved, celebrity-seeking, reality TV-show-wannabe folks take selfies. But that is an oversimplification of a visual culture phenomenon that has changed the way we communicate with others.

Selfies Today

In 2025, the selfie is more ubiquitous than it was in 2017, before TikTok and Instagram reels. TikTok has 1.8 billion monthly active users, while Instagram has over 2 billion. That’s a lot of selfies.

But one of the primary reasons our selfies look different today is — unsurprisingly — the rapid ascent of artificial intelligence.

In April, OpenAI rolled out image generation capabilities in ChatGPT. Social media was quickly flooded with AI-generated images in the style of Studio Ghibli, the latest in a long line of trends that require people to give AI companies access to their faces. Filters and editing apps like Facetune and YouCam Makeup were popularized in the 2010s, but some now use AI to analyze facial features and identify ways to “enhance” them, to both absurd and harmful effect. The Tumblr aesthetic is out, and subtle AI-powered filters are in. It’s easier than ever to make yourself conventionally pretty for a selfie.

The tourism industry and art institutions have been concerned about selfies, too. In 2015, the Metropolitan Museum of Art boldly banned selfie sticks. Around the same time, a museum in Manila created an interactive art museum designed specifically for taking selfies. Last month, a visitor accidentally tore a hole in a 17th-century portrait while attempting to take a selfie at the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, Italy, part of a trend of museumgoers backing into artworks while snapping selfies.

Nonetheless, more tourist sites are accommodating ravenous selfie-takers. The city of Barcelona is taking action to ease the selfie mania at Sagrada Família, Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí’s unfinished cathedral. The city recently announced plans to create a dedicated public square where visitors can take selfies before entering the basilica.

People are still using selfies on dating apps, often poorly. It’s common knowledge that if you’re looking for a connection, there are a few selfies you should avoid: bed selfies, gym mirror selfies, shirtless selfies (for cis men), bathroom selfies, excessive group pic selfies, selfies where your ex or a child (yours or someone else’s) has obviously been cropped out. But plenty of people still do this, either because they don’t know how to curate good photos of themselves or don’t want to learn how.

Selfies with celebrities are still everywhere, though fans have gotten more aggressive. Earlier this year, a fan asked Tameka Empson, who plays the “Kimfluencer” Kim Fox in the BBC soap opera EastEnders, to take a selfie at a funeral. In April, Australian cricket player Travis Head turned down a selfie request at a grocery store in India. The video of his so-called “selfie-refusal” went viral. In February, the Brooklyn-based Subway DJ asked comedian Jerry Seinfeld for a selfie and held up his phone accordingly. Then he shouted: “Free Palestine!” Seinfeld replied, “I don’t care about Palestine” and walked away. Subway DJ frowned and posted the video anyhow.

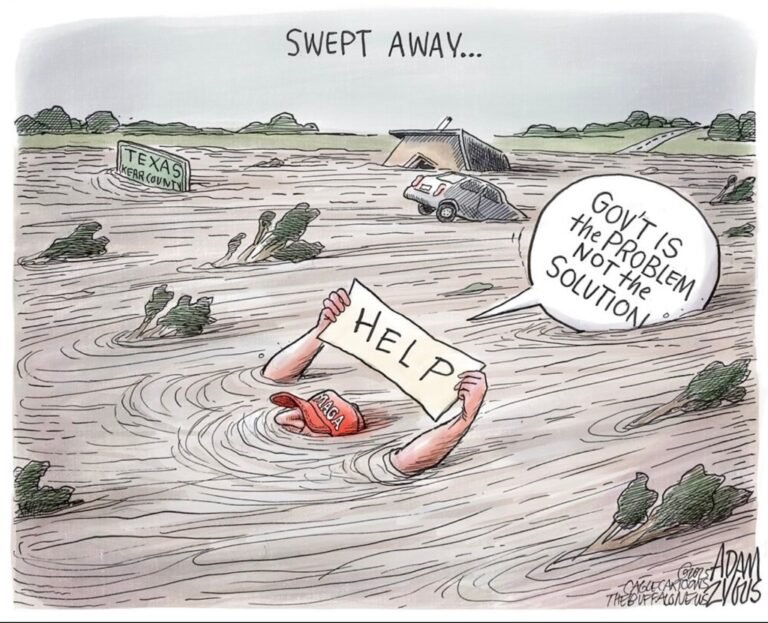

Politicians are also using selfies as power moves.

In March, the US government illegally deported 238 Venezuelan men who they claimed were gang members of Tren de Aragua. Much of this was based on their tattoos and social media profiles. To deport them without due process, Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act — a law enacted in 1789 under then-President John Adams that allows the president to deport and detain immigrants during a “declared war.” They were sent to CECOT, a mega-prison in El Salvador that’s known for human rights abuses. US officials have admitted that they wrongly deported Kilmar Abrego García, who was under protected status. Maryland Senator Chris Van Hollen traveled to El Salvador demanding his release, and was able to meet with him. There’s a photo of them talking over coffee and water, a look of concern in Van Hollen’s face as he leans across the table, but no selfie.

Representative Riley Moore, a Republican from West Virginia, also visited CECOT and got a tour of the prison. But he opted to take a selfie during his visit in April, his blank face visible in front of a cell filled with shirtless tattooed men. In another photo in the same post, he gives two thumbs up in front of the cell, writing in the caption, “I leave now even more determined to support President Trump’s efforts to secure our homeland.”

The photos are vile and dehumanizing; the post received many comments, with people calling the selfie “despicable.” One user said, “I live in your district, and I am disgusted that my representative sees human degradation as a photo opportunity. Shame on you.”

Selfie Futures

When I wrote my book in 2017, the selfie was the new kid on the block and millennials were at the forefront of social media use. But now it’s clear that the selfie is here to stay. Today, growing concerns around selfies and self-imagery as a result of exposure to social media are mostly directed toward Gen Z and Gen Alpha, who are absolutely growing up online. Earlier this year, parents of four British teenagers who died after taking part in the viral “blackout challenge” sued TikTok. The trend circulated in 2022, and now videos or hashtags related to the challenge are blocked. In 2020, the TikTok “skull-breaker” viral challenge came under fire for the similar dangers it posed to kids.

While these aren’t selfies in the traditional sense, they are outgrowths of the core concept of crafting and sharing images of oneself. In 2022, social media companies made around $11 billion advertising to minors in the US, where 95% of teens use social media, according to the documentary Can’t Look Away: The Case Against Social Media (2025). The forthcoming iPhone 17 might get a major selfie camera update, doubling the front camera to 24 megapixels; Androids like the Xiaomi 15 Ultra already have 32-megapixel cameras. Image quality will improve, offering sharper, brighter selfies.

The selfie will continue to circulate, mutate, and connect us with others in unexpected ways, so long as we have smartphones in our pockets. Though it may not always feel like it, the choice to post is ours.