Editors’ Vox is a blog from AGU’s Publications Department.

By the middle stage of a scientist’s career, expertise and reputation have been established, creating space to test out fresh opportunities and expand one’s comfort zone. For three scientists who wrote or edited books as mid-career researchers, this professional stage was very much a “happy medium.” They describe honing their research interests, gaining more autonomy to mold their work life, and finding joy in new roles within and beyond academia. Among these new undertakings was writing or editing a book. In the second installment of three articles, scientists contemplate why a book project was the perfect addition to the dynamic mid-career stage of their professional journeys.

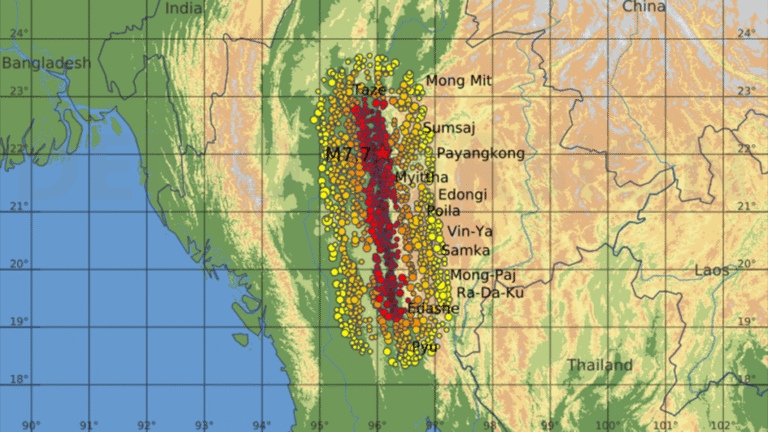

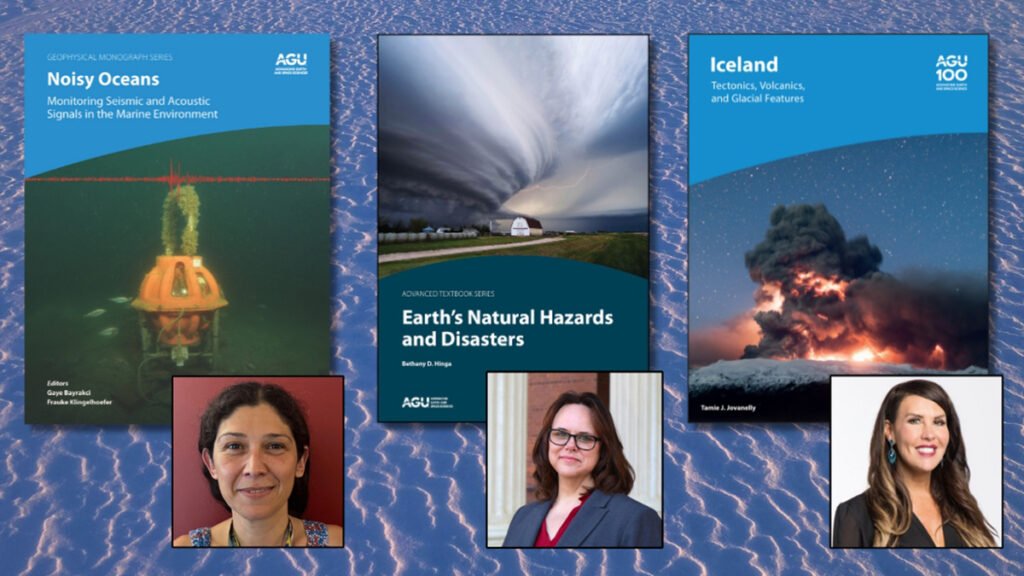

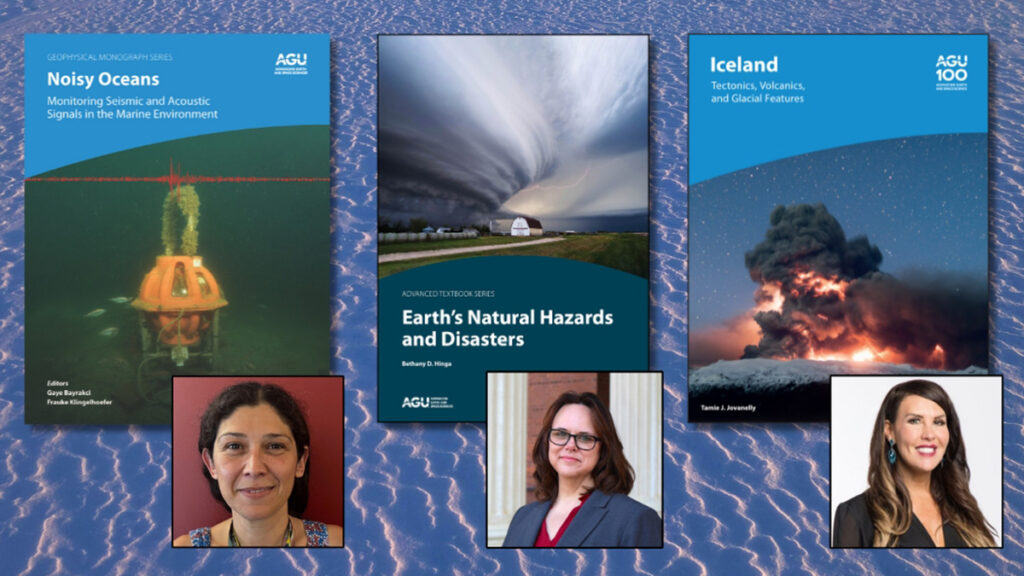

Gaye Bayrakci coedited Noisy Oceans: Monitoring Seismic and Acoustic Signals in the Marine Environment, a comprehensive review of the sources and impacts of different types of marine noise. Bethany Hinga authored Earth’s Natural Hazards and Disasters, a textbook about the science behind natural events and how to prepare for disasters. Tamie Jovanelly authored Iceland: Tectonics, Volcanics, and Glacial Features, which explores the dramatic forces that have shaped the Icelandic landscape. We asked these researchers what developments shaped their mid-career stage, how a book fit in with their other goals and responsibilities, and to what extent their books influenced their next steps.

How would you describe the middle stage of a scientist’s career?

It’s a stage where you’re trusted with responsibility, but you also have the freedom to shape your role.

GB: Mid-career is genuinely exciting. I’m no longer dealing with early-career uncertainty, but I’m still actively thinking about what I want to focus on in the years ahead. It’s a stage where you’re trusted with responsibility, but you also have the freedom to shape your role, whether that’s through supervision, strategic planning, or external engagement. That sense of possibility is one of the best parts of this stage. It is also when you begin to think more about legacy, considering the kind of contribution you want to make in the long run, and that adds meaning and motivation to the work.

BH: I think for a lot of scientists this is the time when research programs and professional relationships are well cemented, and they have a growing bench of graduate students they’ve trained and are moving out into the world to do great things. My experience was different. Ten years post-PhD, I was in higher education administration and starting to branch out into other areas of expertise related to that administrative work.

Why did you decide to complete a book project? Why at that point in your career?

TJ: I decided to write a book after leading a field studies course in Iceland for over a decade. Throughout this time, I noticed a significant gap in the textbook market. While several publications touched on Iceland’s volcanology at a basic level, none provided a comprehensive overview of the island’s tectonics, volcanics, and glacial features. Recognizing this need, I felt compelled to contribute a resource that would serve both educators and students in the field of geology. My prior course preparation not only solidified my understanding of Iceland’s unique geological landscape but also allowed me to organize this knowledge effectively.

It was a chance to do something creative rooted in my scientific discipline.

BH: I had a twelve-month position in Academic Affairs at my university and the students and faculty were only on campus for nine months. I had three months of the year with time on my hands and a deep desire to start on a book that had been simmering in my head for years. I also had incredibly talented colleagues who were willing to write chapters in areas I felt were important to include in the book, but I didn’t have the expertise or comfort level to write myself. It was a chance to do something creative rooted in my scientific discipline, and it was a welcome change of gears from my job during the academic year, which had nothing to do with my discipline.

GB: The idea came when someone in my professional network, Frauke Klingelhoefer, was invited by AGU to propose a book on short-duration or non-earthquake seafloor signals. She contacted me, and we quickly realized that a broader book on ocean noise would be more valuable. It is a timely topic, relevant to biology, climate, defense, and offshore infrastructure, yet still underrepresented in the literature. Frauke, being very busy, suggested we co-edit and encouraged me to take the lead. It felt like the right moment to take on a creative, community-focused project.

What were some benefits of doing a book as a mid-career researcher?

It helped me see connections across disciplines and engage with researchers I might not have otherwise worked with.

GB: Editing the book gave me a much broader view of how scientists use pressure and sound to study both the water column and the shallow subsurface. It helped me see connections across disciplines and engage with researchers I might not have otherwise worked with. It was also a chance to step back, reflect on my own work, and rethink my scientific direction. I’ve since started new collaborations and found ways to apply similar techniques in my projects. The process confirmed that there’s still so much space to grow at mid-career.

TJ: Writing a book as a mid-career researcher offers several significant benefits. First, at this stage in my career, I had successfully navigated key responsibilities toward earning promotion and tenure. With these milestones behind me, I had the freedom to pursue projects that genuinely interested me making the writing process very enjoyable. Second, after years of publishing scientific journal articles, I had honed essential skills in conducting literature searches, synthesizing scientific arguments, and formulating key questions. These competencies not only streamline the writing process but also bolstered my confidence as an author. I felt capable of presenting complex ideas in a manner that is accessible to a broader audience. Third, writing a book allowed me to establish myself as a thought-leader in my field. By compiling my insights and research findings into a cohesive monograph, I have solidified my reputation as an expert on specific topics. This has led to greater visibility within the academic community, opened doors with new collaborators, and presented countless speaking engagements and other professional opportunities.

What advice would you give to mid-career researchers who are considering writing or editing a book?

Writing a book is an excellent way for a mid-career researcher to fall in love with science again.

TJ: My advice for any mid-career researcher considering writing a book is to realize that you are not an expert before you write the book; you are an expert after you write the book. Tackling a book project with this mentality automatically provides you with some grace when you are asking questions that you don’t yet have the answers to. Writing a book is an excellent way for a mid-career researcher to fall in love with science again, and it will make you a better classroom teacher and science communicator as a result.

BH: This is really the perfect time in your career to take on a project of this type!

—Gaye Bayrakci (g.bayrakci@noc.ac.uk, ![]() 0000-0003-1851-5021), National Oceanography Centre, UK; Bethany Hinga (Beth.Hinga@Newberry.edu,

0000-0003-1851-5021), National Oceanography Centre, UK; Bethany Hinga (Beth.Hinga@Newberry.edu, ![]() 0000-0003-0694-5331), Newberry College, USA; and Tamie Jovanelly (tamiejovanelly@gmail.com,

0000-0003-0694-5331), Newberry College, USA; and Tamie Jovanelly (tamiejovanelly@gmail.com, ![]() 0000-0002-4374-0266), Adventure Geology Tours, USA

0000-0002-4374-0266), Adventure Geology Tours, USA

This post is the second in a set of three. Learn about leading a book project as an early-career researcher. Stay tuned for the third installment.

Citation: Bayrakci, G., B. Hinga, and T. Jovanelly (2025), Mid-career book publishing: bridging experience with discovery, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO255026. Published on 20 August 2025.

This article does not represent the opinion of AGU, Eos, or any of its affiliates. It is solely the opinion of the author(s).

Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.