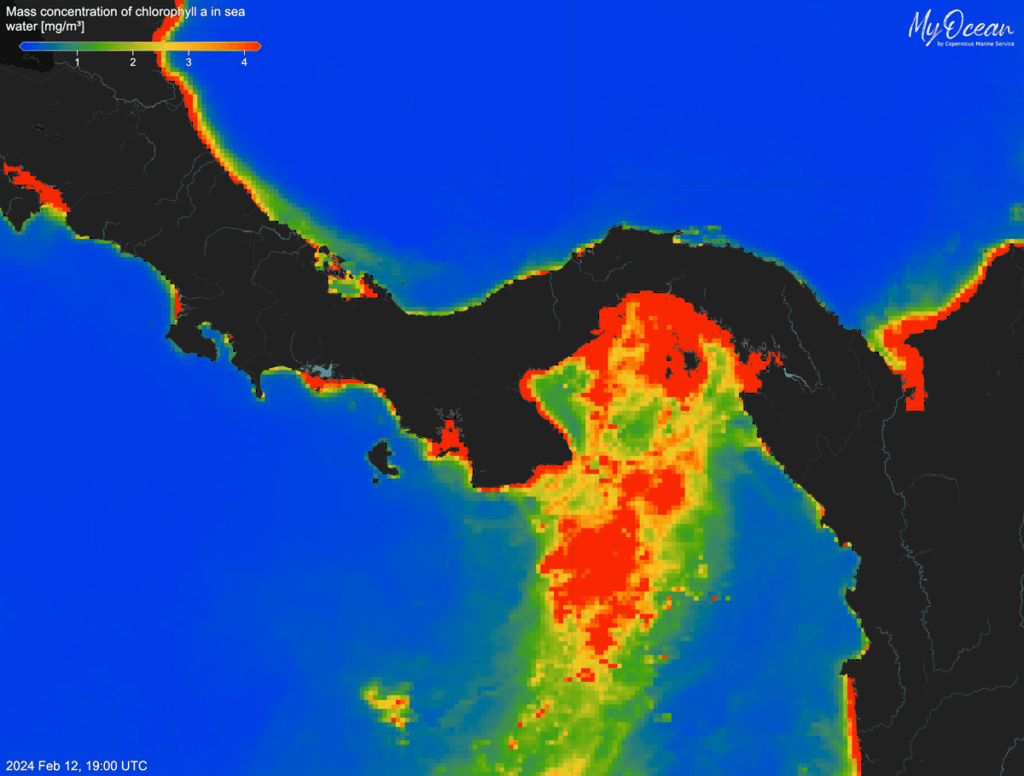

From January to April, strong winds blowing south from the Atlantic side of Panama through gaps in the Cordillera mountain range typically travel over the country and push warm water away from Panama’s Pacific coast. This displacement allows cold, nutrient-rich water to flow up from the depths, a process called upwelling. The Panama Pacific upwelling keeps corals cool and nourishes the complex marine food webs that support Panama’s fishing industry and economy.

In 2025, for the first time on record, this upwelling didn’t occur, according to research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

During the upwelling period early in the year, ocean temperatures near the coast typically fall to a low of about 19°C, said Andrew Sellers, a marine ecologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. This year, the coastal waters reached just 23.3°C at their coolest.

Waning Winds

Sellers said the Panama Pacific upwelling has likely been happening since the isthmus formed millions of years ago. The phenomenon has been recorded at low resolution for 80 years, and scientists have 40 years’ worth of more detailed records.

The team has identified “a shocking extreme event.”

Scripps Institution of Oceanography climate scientist Shang-Ping Xie, who has studied the weather patterns that usually cause the Panama Pacific upwelling but was not involved with this research, said the team had identified “a shocking extreme event.”

Annual upwelling moderates water temperature along the coast and triggers plankton blooms that nourish marine food webs and Panama’s economy. About 95% of the fish the country catches comes from the Pacific side, and most of that marine life is supported by upwelling, said Sellers.

Sellers said that though tropical upwelling plays a critical role in supporting marine food webs and fisheries, it’s understudied. Indeed, it was a happy accident that the research team was able to obtain measurements in 2025. Sellers says the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute maintains a network of temperature sensors near the coast but does not regularly monitor the temperature of deeper waters. Early this year, the Max Planck Institute research vessel S/Y Eugen Seibold was in the region as part of its mission to study the relationship between the atmosphere and the ocean, and it provided high-resolution temperature measurements, including in deeper waters, during the upwelling failure.

These measurements allowed the research team to see that deeper waters offshore were cold as usual but that those waters didn’t make their way to the coast. The cause seems to be a dramatic change in wind patterns in early 2025: Winds hailing from the north were both shorter in duration and 74% less frequent during the study period than in typical years.

Rippling Consequences

“Given how important upwelling is to that region, it’s hard to imagine there wouldn’t be a loss of primary productivity,” the growth of phytoplankton that sustains the ocean’s food chains, said Michael Fox, a coral reef ecologist at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology. “Upwelling sets the stage for the base of the food web.”

Some models have predicted that climate change will cause upwelling in temperate zones such as California to strengthen, but the dynamics in the tropics are more of a mystery. The Panama Pacific upwelling is strongly influenced by the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Sellers says changes in ENSO might be affecting local dynamics in Panama.

“Studies like this one should motivate people to pay more attention to ocean-atmosphere dynamics in the tropics.”

“Studies like this one should motivate people to pay more attention to ocean-atmosphere dynamics in the tropics,” Fox said.

Sellers said this year’s unprecedented upwelling failure is likely to have adverse effects on the country’s vibrant Pacific marine life, but Panama does not collect extensive data on its fisheries. The team is now examining the exception—a dataset related to small fish such as sardines and anchovies—to see whether the lack of upwelling affected those fish.

Xie said the Smithsonian team hasn’t yet provided enough data to evaluate what caused this year’s unusual wind patterns and whether climate change made the upwelling failure more likely. Early this year, La Niña would likely have raised the pressure on the Pacific side of the country, which would have weakened the winds. But Xie said that La Niña is a frequent phenomenon and it alone can’t explain the unprecedented weather seen in Panama this year. He said something likely happened that changed pressure levels on the country’s northern Atlantic side as well. But more research is needed to say for sure.

Sellers’s team is preparing to gather more detailed measurements of marine life effects in early 2026, in case upwelling fails again. They are planning to assess the population of barnacles and other sessile invertebrates, which rely on plankton whose populations burgeon during upwelling.

Though the Eugen Seibold’s mission is set to end in 2026, Sellers said he’s determined to perform extensive water temperature measurements early next year, with or without a research vessel. “Sensors are cheap, and we can get more of them,” he said.

“In coming years, we’ll know if this is going to be a recurring issue,” Sellers said. “If it is, it’s going to be a hard hit to the economy.”

—Katherine Bourzac (@bourzac.bsky.social), Science Writer

Citation: Bourzac, K. (2025), Panama’s coastal waters missed their annual cooldown this year, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250382. Published on 15 October 2025.

Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.