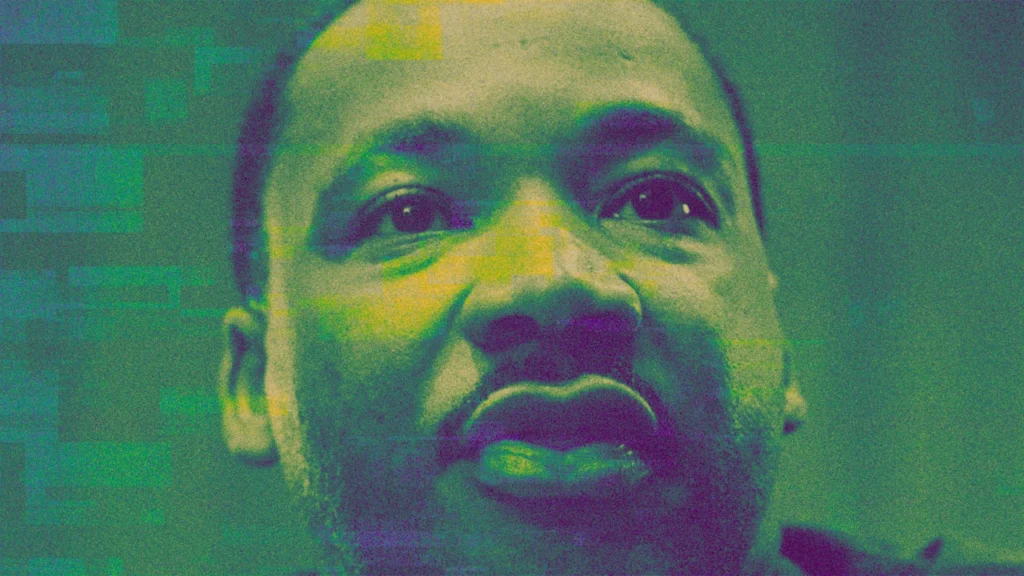

Martin Luther King, Jr., did plenty to change the world for the better. And nearly 60 years after his assassination, he’s at the center of a major concession by the world’s leading AI company that puts a battle over intellectual property and the right to control your image into the spotlight.

In the weeks after OpenAI released Sora 2, its video generation model, onto the world, King’s image has been used in a number of ways that his family have deemed disrespectful to the civil rights campaigner’s legacy. In one video, created by Sora, King runs down the steps of the site of his famous “I have a dream” speech, saying he no longer has a dream, he has a nightmare. In another video, which resembles the footage of King’s most famous speech, the AI-generated version of the civil-rights campaigner has been repurposed to quote Tyga’s ‘Rack City’, saying “Ten, ten, ten, twenties on your titties, bitch.” In another, which Fast Company is not linking to, King makes monkey noises while reciting the same famous speech.

“I can’t say how shocking this is,” says Joanna Bryson, a professor of AI ethics at the Hertie School in Berlin.

Bryson, a British citizen since 2007 but born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, says that the videos featuring the civil-rights campaigner were particularly distasteful because of his role in historical events. “I was born in the 1960s so any kind of atrocity against his memory is incredibly distressing,” she says. “But also, his family is famously excellent and activist in protecting his legacy.”

That activist intervention has resulted in OpenAI rethinking its approach to how people are depicted in Sora. Sort of.

King was far from the only dead individual whose image was recreated and resuscitated with the help of Sora, as Fast Company has previously reported. While the King Estate has managed to secure something of a climbdown from OpenAI in one form—the AI firm said on Oct. 16 it “believes public figures and their families should ultimately have control over how their likeness is used”– the concession is only a partial one. The public statement continues: “Authorized representatives or estate owners can request that their likeness not be used in Sora cameos.”

“This is an embarrassing climb down for a company that just two weeks ago launched a deepfake app that would generate realistic videos of pretty much anyone you liked,” says Ed Newton-Rex, a former AI executive-turned-copyright campaigner and founder of Fairly Trained, a non-profit certifying companies that respect creators’ rights. “But removing one person’s likeness doesn’t go nearly far enough. No one should have to tell OpenAI if they don’t want themselves or their families to be deepfaked.”

An opt-out regime for public figures to not have their images used—some would argue abused—by generative AI tools is a far cry from the norms that have protected celebrities or intellectual property owners in the past. And it’s an onerous requirement on individuals as much as corporations to try and fight fires. (Separately, Fast Company has reported that OpenAI’s enforcement of registering Sora accounts in the names of public figures has been patchy at best.)

Indeed, the huge imposition that such an opt-out regime would have on anyone has been appealed at governmental levels. Following Sora 2’s release, the Japanese government has petitioned OpenAI to stop infringing on the intellectual property of Japanese citizens and companies.

In this instance, it goes beyond IP alone. “This is less of an IP issue and more of a self-sovereignty issue,” says Nana Nwachukwu, a researcher at the AI Accountability Lab at Trinity College Dublin. “I can look at IP as tied to digital sovereignty in these times so that makes it a bit complex. My face, mannerisms and voice are not public data even if—big if—I become a viral figure tomorrow. They’re the essence of my identity. Opt-out policies, however intentioned, are often misguided and dangerous,” she says.

“We simply can’t ask every historic figure to rely on this kind of body to ‘opt out’ of sordid depictions,” says Bryson. “It would make more sense to demand some lower bounds of dignity in the depiction of any recognizable figure.”

Says Newton-Rex: “It’s really very simple—OpenAI should be getting permission before letting their users make deepfakes of people. Anything else is incredibly irresponsible.” Newton-Rex has long been a critic of the way that AI companies approach copyright and intellectual property.

OpenAI has defended its partial stand down by saying “there are strong free speech interests in depicting historical figures.” A spokesperson for the company told The Washington Post this week: “We believe that public figures and their families should ultimately have control over how their likeness is used.”

Bryson believes that some sort of AI-specific approach to how living figures are depicted through these tools is needed, in part because of the speed at which videos can be produced, the low barrier to entry to doing so, and the low cost at which those outputs can be disseminated at speed. “We probably do need a new rule, and it will unfortunately only depend on the brand of the AI developer,” she says. “I say ‘unfortunately’ because I don’t expect the monopoly presently enforced by compute and data costs to hold,” she adds. “I think there will be more, less expensive, and more geographically diverse DeepSeek moments [in video generation].”

Experts suggest that the world shouldn’t necessarily celebrate the King climbdown as a major moment, in part because it still tries to shift the window of acceptability over intellectual property and recognizable individuals further than it stood before Sora was unleashed on the world. And even then, there may still be workarounds: Three hours after OpenAI published its statement in conjunction with the King Estate, an X user shared another video of the iconic figure.

In this one, at least, King’s words weren’t too twisted. But the fact it could be made at all was. “I have a dream,” the AI character said to applause, “where Sora changes its content violation policy.”