Hannah Alsark says that Adobe’s top clients—the owners of some of the most protected, most valuable brands and IP in the world—had a stark message for the company regarding Firefly, its generative AI engine: They wanted more, and they wanted better.

“They told us they actually needed models that understood all their products, all their brands, their creative direction,” says Alsark, Adobe’s VP of GenAI New Business Ventures. “They have characters, they have particular motion styles, and they needed us to train on that.”

Firefly—which uses prompts to create assets across all Adobe’s vector, bitmap, and motion apps—couldn’t do this because it doesn’t understand brands at the IP level. “We consider that a feature, not a bug,” Alsark tells me. Firefly is a generic engine, but Adobe’s top clients need to create millions of assets for dozens of different platforms and marketing media, all of them conforming to their own strict IP rules and brand books.

This is why the company has built a new consultancy arm for Fortune 2000 companies to develop bespoke AI models that could craft hundreds of thousands of images, illustrations, and videos that conform strictly to their IP and creative guidelines. Its name: Adobe AI Foundry.

The million-asset problem

The move comes as a direct response to a mathematical nightmare facing every major brand. Alsark calls it the “combinatorics math problem”. A company with just eight products that wants to market them across 15 channels in 35 languages with a few refreshes a year is already looking at creating half a million individual assets. “With social, we know we’re doing probably three refreshes a week,” she explains. “So the real numbers are in the millions and millions and millions.”

Before now, that scale was simply impossible. Time, budgets, and human resources are all finite. “The only unlock here is responsible AI,” Alsark insists. This crushing demand from the attention economy is precisely why Adobe’s biggest clients, companies like The Home Depot and Walt Disney Imagineering, came to them. They needed an industrial-scale solution, but one that respected their most valuable asset—their intellectual property.

Adobe’s public Firefly model was a start, but it was designed to be IP-agnostic. While brands applauded this safety-first approach, they needed an AI that could learn their world—their characters, their color palettes, their unique aesthetic. Last year’s self-serve “Custom Models” were a step in that direction, allowing companies to train the AI on a single concept, like a specific style or shape. But clients wanted more. They wanted the whole kingdom, not just one castle.

A bespoke AI partnership

Adobe AI Foundry isn’t a piece of software you buy off the shelf; it’s a deep, consultative partnership that feels more like hiring a boutique division of AI experts from Accenture or IBM than licensing a tool. Adobe targets the Fortune 2000, a customer base where it already has deep roots through its Creative Cloud and marketing software suites.

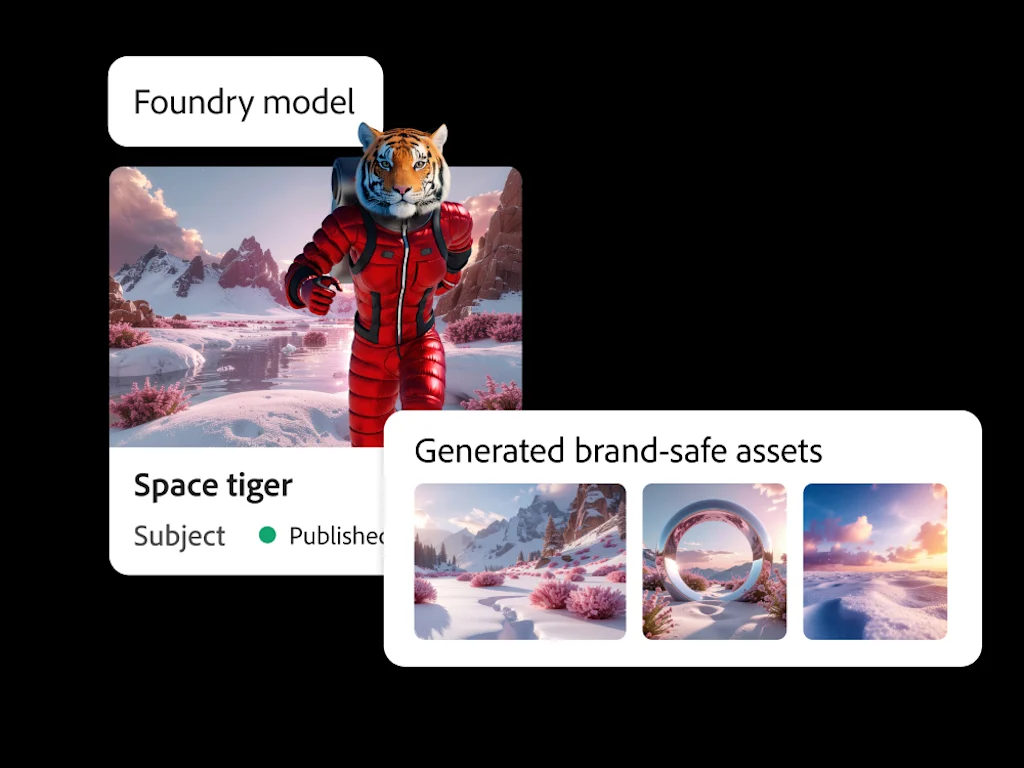

“You actually get a team of allocated experts from Adobe,” Alsark says, listing “applied scientists, engineers, [and] creative workflow experts.” These teams work directly with a client to build a unique generative AI model from the ground up, trained exclusively on that company’s private data and assets.

The process is intensive and can take a couple of months just to get the first results. It begins with use-case discovery, where Adobe’s team identifies the core business problem, whether it’s creating seasonal ad campaigns for a retailer like Amazon Fresh or generating limitless variations of a hero image for a beauty brand like MAC.

Then comes the heavy lifting. Adobe’s engineers “surgically reopen” their foundational Firefly models to retrain them on the client’s proprietary IP, a process involving billions of parameters. After months of training and untold GPU cycles and consumed watts, the final model inherits all the world knowledge of the base Firefly engine but is then overfitted to speak the client’s brand language fluently and exclusively. The output is locked down; it belongs to the client and will never be mixed with another company’s data.

The trust factor

The entire proposition hinges on two things Adobe believes it alone can offer at this scale: commercial safety and seamless integration. The company has been careful to build its foundational models on licensed Adobe Stock data, shielding its clients from the copyright nightmares that have plagued other AI models. Foundry extends that protection by creating a secure vault for a brand’s own IP.

This focus on safety and its existing enterprise presence is Adobe’s strategic moat against competitors like Canva, which is also aggressively pursuing the corporate market. When I bring up the competition, Alsark doesn’t seem to be concerned. She claims that clients came to Adobe after experimenting with everything from startups to hyperscalers because they trust Adobe to understand the entire creativity landscape.

“They are already deeply into our creative tools. We’re in their marketing stack, and we are enterprise-grade,” she says. The ability to plug a custom, brand-aware AI model directly into the Photoshop, Illustrator, and After Effects workflows that a company’s creative teams already live in is a killer advantage. Molly Battin, the CMO at The Home Depot, an early Foundry customer, calls it “an exciting step forward in embracing cutting-edge technologies to deepen customer engagement.”

For an old guy like me, tired of seeing Silicon Valley promising revolutions every other week, this feels different. The initial AI craze, as I called it in my chat with Alsark, is still about public-facing tools that felt like creative toys. For most of us, anyway. Adobe AI Foundry represents the next, far more serious phase: AI is being forged into a bespoke, industrial-grade weapon for the world’s biggest brands.

It’s no longer about a single person creating a wild image or helping with a creative roadblock; it’s about a corporation generating a million on-brand assets before lunch. It’s less of a craze and more of a quiet, brutally efficient corporate takeover of the creative process.