There was a time when Congress took its constitutional prerogatives seriously. Today, it is at best a cheerleader for President Trump — never more so than when he acted alone last week to take the nation to war.

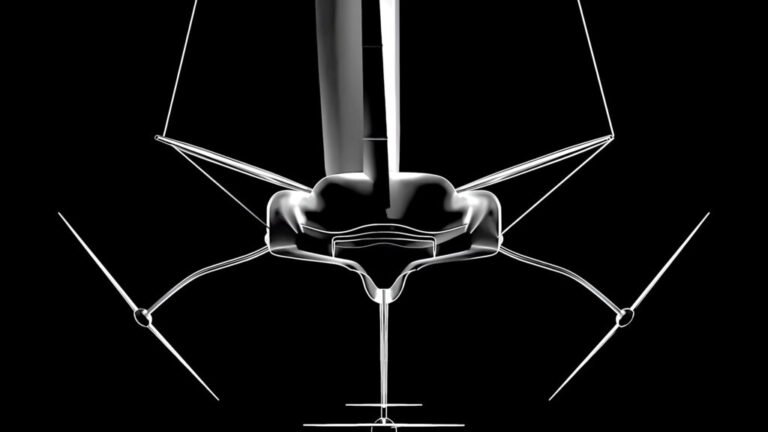

Whatever the merits of the attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities — and the jury is still out on whether it achieved its purpose — there should be no doubt that Trump exceeded his authority in taking the nation to war without congressional approval.

Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) dismissed the charge that the president acted unconstitutionally, citing his Article II commander in chief authority. That may sound plausible to the uninformed, but it is a gross misreading of the Constitution.

When the Founders considered this issue in Philadelphia in 1787, the original language in Article I was “Congress shall make war.” The delegate from Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry, suggested that the word “make” be changed to “declare.”

Gerry argued that the president should be allowed to “repel a sudden attack on the United States,” thus the word “make” was too restrictive.

This may sound like a debate reserved for a class in constitutional law, but in the early 1970s, Congress held many hearings as members considered the language of the War Powers Act. That law makes it clear that Trump should have consulted Congress and sought its authority before going to war with Iran.

There is no question that Congress has allowed its war powers to erode in the past several decades. American forces have been deployed around the world and the president has a legitimate responsibility to protect them. In addition, after 9/11, a broad authorization was given to the president to pursue non-state terrorists wherever they might be.

President George W. Bush requested an Authorization for Use of Military Force when he decided to invade Iraq in 2002. Congress approved that mission, even though many members came to regret that decision, as it was based on faulty intelligence that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction.

President Barack Obama committed U.S. troops to a NATO mission in Libya in 2011. He didn’t request congressional consent, arguing that the U.S. mission was to support NATO forces logistically and that troops would not be engaged in hostilities. He conveniently ignored the phrase in the law requiring consent in “situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is likely.”

Presidents have found clever ways to avoid consulting with Congress and triggering the provisions of the War Powers Act.

President Reagan deployed Marines to Lebanon in 1982 as part of a multinational peacekeeping mission. When the U.S. took sides in the civil war, the peacekeeping rules of engagement were never changed. According to Admiral Robert Long’s after-action report, the failure to change the rules of engagement left the Marines unprepared for the terrorist attack that killed 241 of them.

In 1986, Reagan sent a naval task force into Libya’s Gulf of Sidra, knowing that Libya would react. When lawyers suggested that he might have to consult with Congress, the wartime rules of engagement were rewritten. U.S. fighter aircraft were told that they could not fire on Libyan planes unless fired upon. The risk to our aircraft wasn’t large, and the change in the rules of engagement was considered worth avoiding a need to consult with Congress.

There is no indication that President Trump or his advisors even considered the possibility of requesting congressional authority to attack Iran. Reportedly, a few senior Republican leaders were informed that the B-2 bombers were on the way.

The administration did notify Congress after the fact, as is required under the War Powers Act. However, Congress could have acquired more details from the press.

President Trump seemed to enjoy the suspense he created when he said he would decide whether to join Israel’s war with Iran within two weeks.

”I may do it. I may not do it. I mean nobody knows what I’m going to do.”

Now it is done, and he claims to have “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear capability. But has he? We don’t really know at this point. Has Iran spirited away enough highly enriched uranium to build a bomb? A leaked intelligence report contradicts the president’s claims.

The U.S. and Iran were engaged in negotiations to end any possibility that Iran would build a nuclear weapon. The president said that he had given Iran 60 days to capitulate and eliminate all enrichment. Yet the U.S. and Iran had scheduled a negotiating session in Qatar for June 15, two days after the 60-day period expired.

Reliable intelligence sources have reported that Iran’s enrichment to a 60 percent level was concerning, but that was still short of the 90 percent enrichment needed. There was still no evidence that the Iranian leadership had decided to build a weapon, let alone a delivery system. That would have taken considerably more time.

A recent report by the International Atomic Energy Agency stated that Iran’s enrichment efforts were not in compliance with the Non-Proliferation Treaty. That was troubling, but that report was also an indication that the agency’s monitoring was intrusive and reliable.

Neither the International Atomic Energy Agency report nor the intelligence community assessment contained evidence of an immediate threat to the United States. In the aftermath of the U.S. attack, diplomacy may still be possible, but it is also possible that Iran will now go ahead and build a bomb.

Perhaps now Congress will look back and reflect on what it means to give a single human being so much power. If this breach of the constitutional order is allowed to pass without further introspection, how will Trump exploit this unchecked power in the future?

The Congress was created as the branch of government assigned the responsibility to “declare war,” to “make all laws necessary and proper” to implement the Constitution and to oversee the executive branch. It wasn’t created to be a cheerleader for an unbound president.

J. Brian Atwood served as assistant secretary of State for congressional relations and was foreign policy advisor to Senator Thomas Eagleton, a principal author of the Senate War Powers Resolution.