LOS ANGELES — Barbara T. Smith presses her face up to the glass. The tip of her nose is squashed and skewed, exaggerating the size of her nostril. Her full smile shows off two rows of slightly imperfect teeth. Wisps of hair curl across her closed eyes, clamped tightly so as not to be blinded by the light of the Xerox scanner.

“Just Plain Facts” (1966–67) marks the beginning of Smith’s illustrious career as an artist. Years before her name became synonymous with feminist performance art, Smith, then a housewife on the verge of a collapsing marriage, channeled her feelings through a copy machine. She leased a Xerox 914 scanner, set it up on her kitchen table, and produced more than 50,000 artworks within one year.

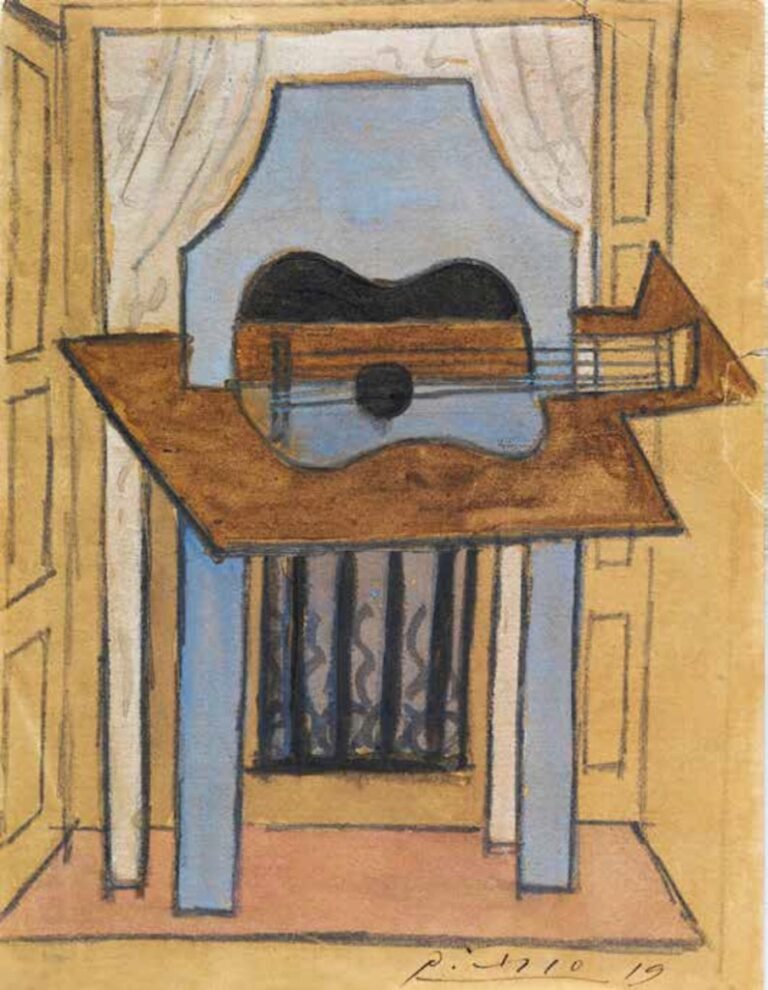

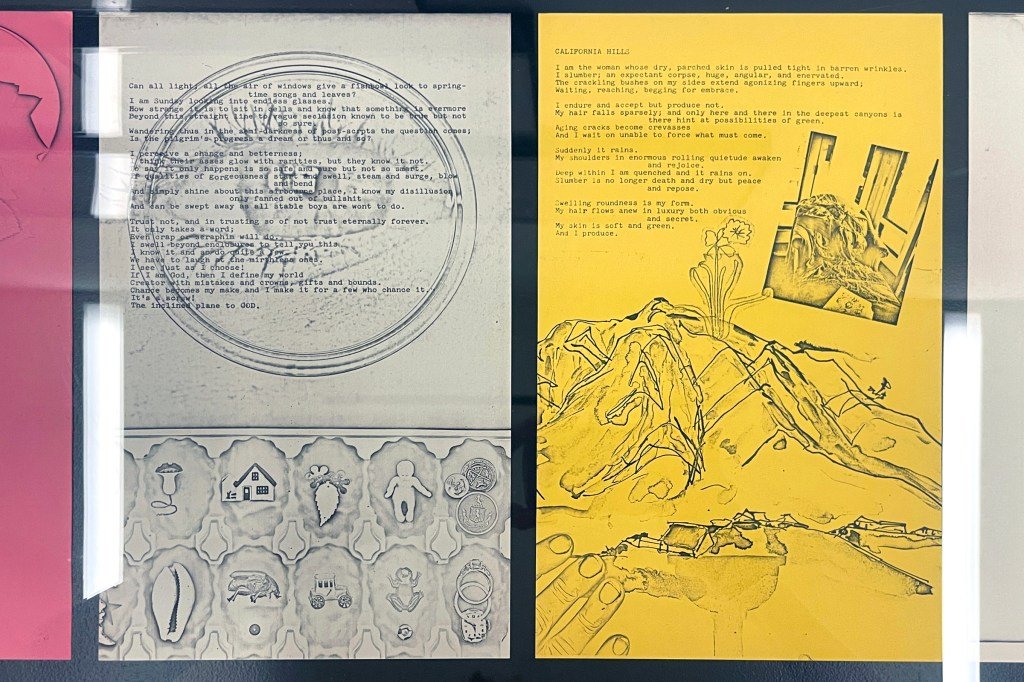

A portion of these works is currently on display in Barbara T. Smith: Xerox 914 at the Marciano Art Foundation’s library, which showcases Smith’s thorough experiments with Xerox’s capabilities. She scanned photographs, toys, and her own body to make a varied set of poetry zines and prints. She treated the machine like a lithograph, often running prints through the copier multiple times to continuously add to its composition. This was the process through which she created four hands on a single page within the publication “In Self Defense” (1966–67). In a meta-gesture, the palms read “copy” and “unique.”

Smith also tested the technology’s limits by re-copying material until the image degraded, and playing with the distance between object and surface. She created faded effects by partially lifting up photographs within the pages of “Rebellion” (1965–66), emulated a sluggish trail by dragging a calculator mid-scan in “In Self Defense” (1965–66), and produced an X-ray effect in her poetry book “Joy” (1965–66) by layering images behind transparencies and plexiglass.

Most of these images were collated into publications. 30 spiral-bound books make up her Coffin series, and five unbound books create Poetry Set, which includes both “Joy” and “Rebellion” (both series 1965–66).

The works in which Smith’s body appears are particularly exciting, as they signal her future in performance. The three prints that make up “Self Portraits” (1966–67) show her hands and face smashed against the glass alongside a seashell and a fern, evoking a sense of drowning.

In one of the works entitled “Self Portraits” (1966–67), Smith’s breast is pressed firmly against the glass, making up the lower third of the composition. She goes on to illustrate similar forms in other pieces by directly marking layered mylar transparencies with a marker, and others where the breast, set against a rippling, abstract pattern, progressively becomes smaller. These works resemble mammograms, another new technology of the ’60s. Though they are recommended for middle-aged women, and Smith was only in her 30s at the time, I can’t help but draw an association between the medical scan and the comparatively late age at which she began her career.

At 82, Smith revisited the photocopy machine. “Untitled” (2013) features scans of her hands, modern technology capturing her veins and wrinkles in high definition, emphasizing her age. After copying her hand, she embellished the paper with colorful glitter. Gold, green, and silver sparkles shoot out of her hands, a sorceress casting a spell. Once she discovered the Xerox, Smith never stopped exposing herself — to the light of the bulb, and to the world through art.

Barbara T. Smith: Xerox 914 continues at Marciano Foundation (4357 Wilshire Boulevard, Mid-Wilshire, Los Angeles) through July 5. The exhibition was curated by Jenelle Porter.