Since Saudi Arabia’s comprehensive Vision 2030 development project launched in 2017, the quaint yet historically significant desert town of AlUla has emerged as an important cultural hub for the rapidly “opening-up”

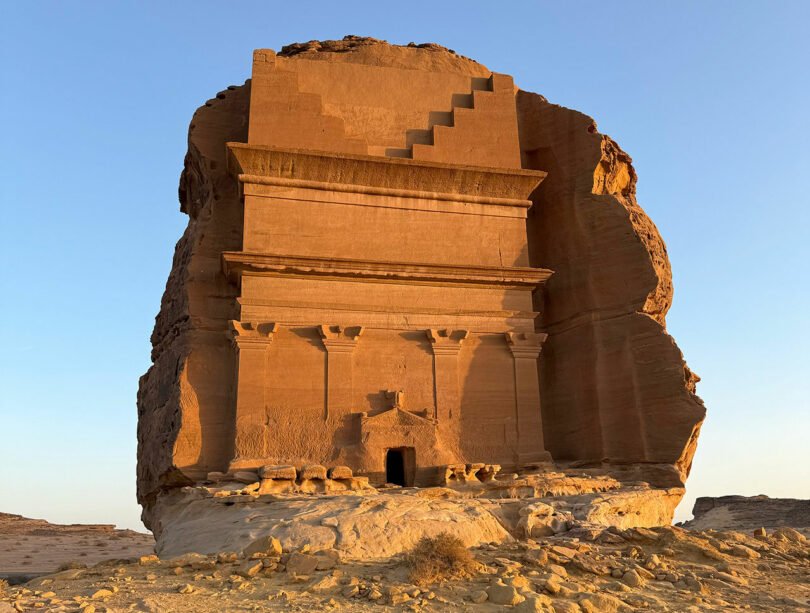

kingdom. Nestled amid soaring wind-formed limestone cliffs, the verdant date-palm oasis was once a stop-over for muslim pilgrims heading south toward the holy cities and before that, incense traders from southern Arabia traveling north to the Fertile Crescent. The well-preserved adobe-style settlement here dates back 900 years. The iconic Hegra tombs nearby—erected by the same civilizations as Petra—are at least 2100 years old.

While it might not be as glittering as other Vision 2030 projects—The Line, for one—the multifaceted AlUla project is significant in its own achievement, but perhaps also as a model for other similar civic initiatives in the kingdom, region, and beyond. The Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU)—branded as Arts AlUla for several incorporated projects—focuses its efforts in three areas: cultural preservation, ecological restoration, and new artistic endeavor.

The latter, in particular, centers on bringing international actors into the fold. “It’s very much about transferring knowledge but also showcasing what we have here and the unique ways we’re accomplishing our goals,” says Hamad Alhomiedan, RCU’s arts and creative industries director, “Everything we do should be accessible, not just across the kingdom or the region, but globally. We’re here to regenerate the area and that requires a lot of work. It’s essential to have help from a diverse group of cultural platforms and independent talents, even scientists. We’re developing a new playbook so to speak.”

And while the recent establishment of “artisanal” workshops/boutiques in the old city might seem slightly contrived, other projects like the AlUla Artist Residency program are impressive in both their international scope and experimental foundation; deeply rooted in the cultural and ecological heritage of place but universal in the proposed application of outcomes.

The 2025 edition focused on design and brought five up-and-coming to mid-career practices to AlUla for a three month intensive. Hailing from Saudi Arabia, Côte d’Ivoire, Tunisia, Belgium, and the Netherlands, these contemporary studios—all speculative and craft-led in ethos—conducted thorough ethnographic and material research. The resulting designs distill from investigations of local daily life, emergent industrial developments, and the clever harnessing of natural resources abundant here.

Curator Dominique Petite-Frère—founder of multivalent exhibition platform and creative incubator Limbo Accra—ensured that these concepts did not remain nebulous. Each proposal comprises actual furnishings, some that could easily be introduced into the immediate context with a bit more tooling.

Analysing the idiosyncratic intricacies of the limestone rock faces found here but also how local children interact with public infrastructure, Riyadh-based designer Aseel Alamoudi created 3D-printed, extruded sand benches. These non-prescriptive public structures are meant to be climbed on; hinting at Alamoudi’s larger ambition of constructing a massive playscape on the desert floor.

Brussels-based Ori Orisun Merhav redirected the local, age-old tradition of harvest palm leaves and, combined with hardening properties of shellac, developed a new formal vocabulary of naturalistic lamps, carpets, and stools. Palm as a material was also central to Abidjan-based talent Paul Moustapha Ledron’s collection of an almost ancient architectonic daybed, incense altar, and palm tree-like floor Tamaro Jar lamp. The designs take on ceremonial, even spiritual qualities; objects that facilitate a “slowing down” of sorts, allowing oneself to be fully immersed in the environment.

Unveiled as part of the Alula Arts Festival, which ran until February 14, the five collections join new design concepts presented at the French Ministry of Culture’s Villa Hegra complimentary residency program. The downtown AlUla institute is managed by AFALULA (French agency for development in AlUla).

For the repurposed estate’s five allocated studio spaces, French designer Paul Emilieu Marchesseau imagined a series of modular furniture pieces with materials sourced neraby—both natural and industrial. As evidenced in the curtain-enclosed lamp, these propositions are equal parts function and poetry; carrying the trace of local traditional ornamentation as a grounding element. The collection is site-responsive on both an aesthetic and practical level; the latter also becoming more universal in potential application.

Also on view, is the fourth biennial instalment of Desert X AlUla, the offshoot event of the California outdoor installation art exhibit. Like the two other showcases, the significantly larger works presented also respond to context.

“AlUla’s landscape is a living archive of stories, traditions and encounters that span centuries,” said Desert X co-curator Wejdan Reda. “For this edition, artists have engaged with its valleys and historic routes to create works that honor its landscape while opening new spaces for imagination.”

Of note was Mohammed AlSaleem’s series of metal totems, extracting the formal symbols—the geometry of the crescent shape—found in sacred spaces—mosques—across Saudi Arabia. Placed in the natural context of Desert X AlUla’s chosen Wadi valley, the works are de-contextualized from their primarily urban settings but suggestive of what lies beyond the horizon.

Comprising larger-than-life, cast foam Desert Hyacinths and their secondary leaves, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pon’s Imole Red installation comes together as a forum; another type of sacred space, and like Paul Ledron’s furnishings, inspiring visitors to take stock of its surroundings and engage their mystical qualities.

Many as international interlocutors, of sorts, the talents exhibiting across these showcases were able to introduce elements of their own cultural backgrounds as corresponding cues to those they uncovered here.