When it comes to EVs, a bigger battery isn’t always better.

Ford Motor Company is making that bet as part of its effort to manufacture a new suite of more affordable electric vehicles—beginning with a $30,000-starting-price mid-size electric truck set to launch in 2027.

To get more out of a smaller battery, Ford has had to reimagine every step of its manufacturing process. It has scrapped the typical assembly line process in favor of what the automaker calls its “Ford Universal EV Platform,” and simplified every part of its EV, from the miles of wiring inside the electric system to the number of parts that make up its frame.

And it’s had to rethink the battery itself, to make it both more efficient and less expensive to produce. Ford credits many of those innovations to the team from Auto Motive Power, an EV charging startup Ford acquired back in 2023.

Ford Bounties to increase efficiency

Batteries are a massive challenge to designing affordable, efficient EVs. The battery makes up at least 25% of an EV’s total weight and around 40% of its total cost.

In recent years, EV batteries have kept getting bigger. A bigger battery can add miles to an EV’s range, but that also means adding more weight, which makes an EV less efficient, and potentially more difficult to handle. It also means more production costs, which could make that EV more expensive.

To make more affordable EVs, then, Ford has rethought every part of its EV in service of that battery.

Every engineer, whether working on the vehicle’s aerodynamics or its interior ergonomics, uses metrics that Ford calls “bounties” to weigh design tradeoffs in terms of how they affect the vehicle’s range and battery costs.

That has led to a “system-level optimization that the team has done to turn over every rock to find dollars of cost and watts of efficiency,” says Alan Clarke, executive director of Ford’s Advanced EV Development department.

Ford removed 4,000 feet of wiring from its Universal EV Platform, for example, shaving off 22 pounds compared to the wiring used in Ford’s first-gen electric SUV. While the Ford Maverick has 146 structural parts in its frame, Ford’s forthcoming midsized EV will have just two parts, thanks to a lighter and simpler “unicasting” process.

A more efficient battery

Besides the design tradeoffs it made, Ford also redesigned its battery to make it both smaller and more efficient. That can translate to a better range and charging experience for customers, too.

“The pipe of electrons coming out of the wall is always the same for every customer,” Clarke says. “But how many miles that translates into is directly defined by efficiency of the power electronics and efficiency of the vehicle.”

In its forthcoming midsized EV, Ford will use lithium-iron-phosphate, or LFP, batteries. With no nickel or cobalt, these batteries—which are common in Chinese EVs—use less expensive chemical ingredients than lithium ion and other battery types.

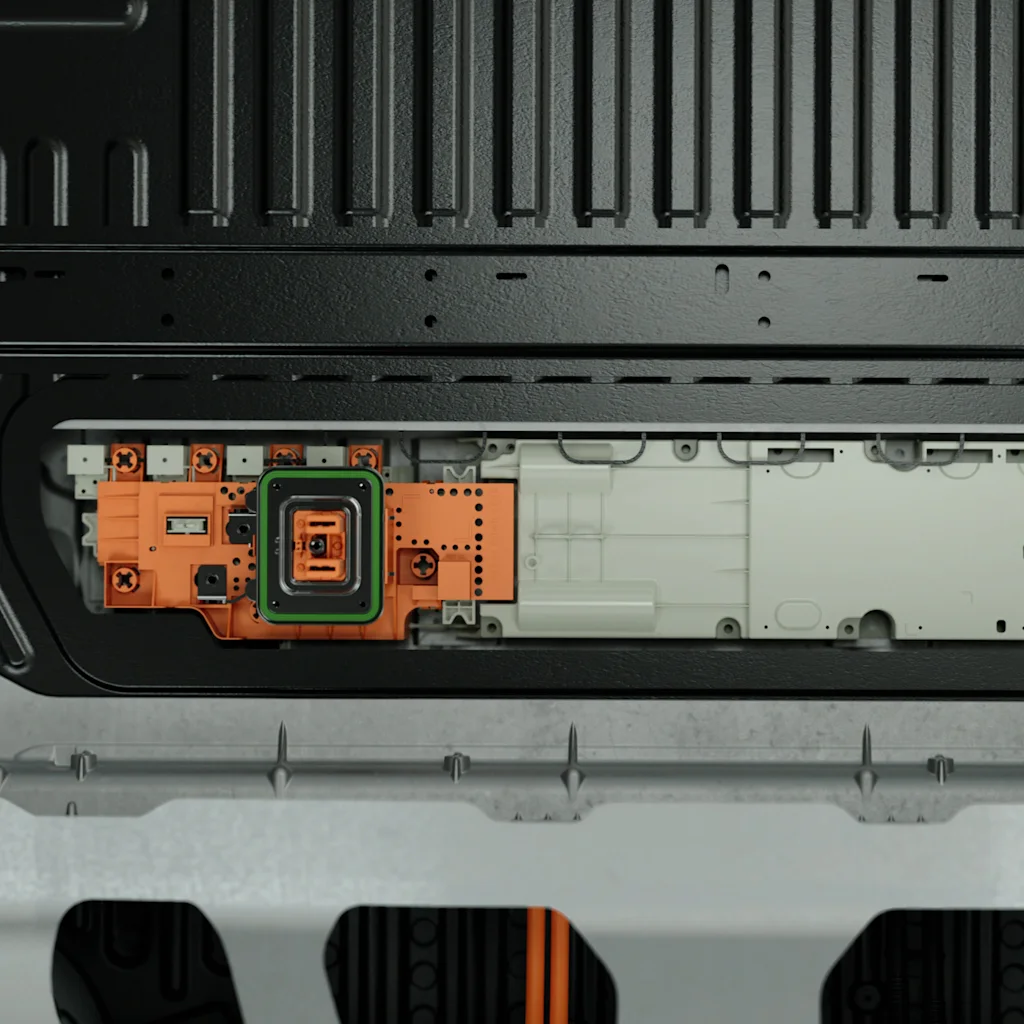

How efficient an EV battery is depends largely on its software, and that’s where the team from Auto Motive Power comes in.

An EV battery pack is composed of multiple cells, and “the performance of that battery pack is limited by your worst cell,” Clarke explains. Battery cells are sensitive to temperature, voltage, and other conditions around them.

“You want to buy [an EV] from whatever company understands their batteries the best, thermally manages them the best from a software standpoint, can measure where they are and balance them and charge them at the rates that don’t deteriorate them,” he adds.

Algorithms can monitor a battery’s voltage, temperature, and regenerative braking in order to maximize the vehicle’s energy use.

Software controls how an EV takes energy out of its battery and puts it into the vehicle’s drive unit. And it also allows the automaker to optimize a battery in real time, responding to the driver’s behaviors and real-world data to reduce battery degradation and protect its lifespan.

“Each customer has different ways of utilizing batteries,” explains Anil Paryani, formerly the CEO of Auto Motive Power and now an executive director of engineering at Ford.

“In Arizona, they might have different heat challenges . . . so we have user-optimized controls to minimize those trade offs,” he says.

Sometimes customers just have different charging behaviors. For example, Paryani says that his mom lives in a condo, and so she almost exclusively uses fast chargers, which can negatively impact an EV’s battery life.

“What do we have to do to avoid [battery] deterioration?” he says. “We are addressing that with our software.”

Ford is making its battery cells at its BlueOval Battery Park in Michigan.

Staying a startup inside Ford

Auto Motive Power was founded in 2017, and was previously a supplier to Ford before it was acquired by the automaker in 2023.

At the time, the team was still operating as a “very scrappy” startup, Paryani says. Becoming part of a $56 billion automaker could have drastically changed that, but they were able to maintain that startup energy.

Executives decided to keep the team “walled off,” Paryani says, “so that we can take design risks that I don’t think traditional auto companies would ever think of taking.”

Big companies like Ford can often get caught up in “analysis paralysis,” Clarke admits, while startups are known for failing fast. Paryani and his team held on to that ethos, while taking advantage of Ford’s resources, like access to its EV development center.

“[Through] all of the different things that Anil’s team have tried, we’ve learned so much about different materials, interaction between different devices, that we wouldn’t have,” Clarke says. “Or in order to learn it, we probably would have spent two years building models and realizing it wasn’t a good idea.”

Paryani’s team, instead, tried out multiple ideas quickly through prototypes. This work is crucial to developing better EVs, which are ultimately still an early technology.

“Internal combustion engine vehicles have had 120 years of maturation, of engineering work, of optimization, of innovation, that have gone into them,” Clarke says.

EVs, by contrast, are in “inning one—or maybe inning two.”