ROME — Finally a modern and critical exhibition about the Baroque in its global context that explores the ways Roman and European artists and intellectuals approached the world beyond Europe. To be sure, the lens through which Europeans viewed the rest of the world was tinted with religious bigotry and an unexamined superiority. Yet it was coupled with the wonder and amazement of discovering the existence of distant civilizations, and and a sense of wonder is excellently expressed in the well-conceived Global Baroque: The World in Rome in the Age of Bernini at the Scuderie del Quirinale. Perhaps the self-defined center of culture that was Rome in the 17th century could, after all, learn something from beyond the bounds of the known.

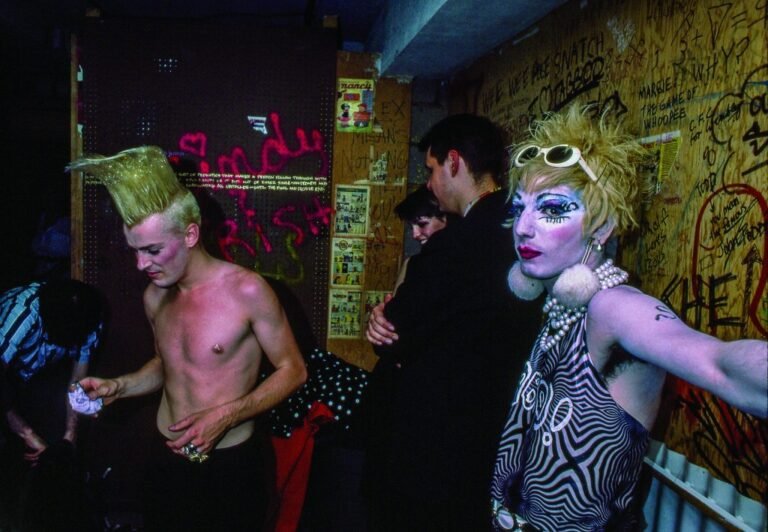

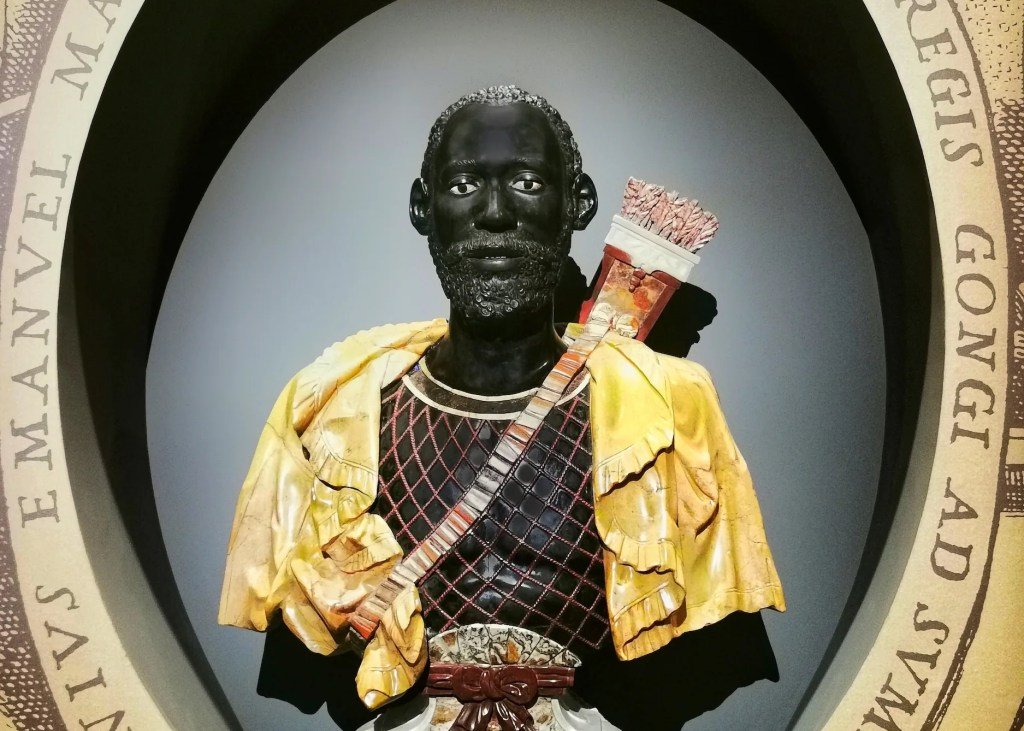

The story told by curators Francesca Cappelletti, director of the Galleria Borghese, and Francesco Freddolini, an art historian at the Sapienza University of Rome, begins with dramatic urgency. Antonio Ne Vunda, ambassador of the Christian king of the Congo, was set to arrive in Rome in early January 1608 with a ceremonial entrance followed by a long procession evoking the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6. Unfortunately, the young ambassador died before his formal entry and his procession became a weird mixture of Biblical tableau and funeral. Ne Vunda’s funerary portrait by the Roman sculptor Francesco Caporale is the first object on display, taken from its usual site in the baptistery of Santa Maria Maggiore (the same church where the late Pope Francis is buried). Even though he was dressed in the Spanish style when he died, he was depicted in his funerary portrait as a Congolese nobleman wearing a cloak over a string vest called a nkutu and carrying a quiver of arrows, the latter signifying a primitive “barbarian” culture. In death, this Catholic representative of a Catholic monarch was othered for the political purpose of showing how the pope’s power extended across the Mediterranean and into the heart of Africa.

A broad-based missionary effort spread from Rome across what the Romans considered the world’s unknown lands in the early Baroque period, and this exhibition shows its successes — for example, a splendid Chinese copy of the medieval Roman icon of the Salus Populi Romani, the “Health of the Roman People,” from about 1600 — and its failures, like Johann Heinrich Schönfeld’s “The Three Jesuit Martyrs of Nagasaki” (1643–44). Local cultures and religions fought back against the expansionism of the Catholic Church, whose victory was far from assured, and which had the unpleasant habit of backing up its proselytism with Portuguese gun-ships, turning a religious issue into an overtly political and military one.

After a strong beginning, the exhibition develops a fascinating centripetal energy, drawing the rest of the world toward Rome. The first section explores Africa and Egypt in the world of the Baroque, two regions that had interested Europeans from the ancient Greeks onward, and that the Romans had wholly or partly conquered. Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa with its dark-skinned inhabitants, was represented in European art as intensely other, whereas Egypt, for so long part of the Roman empire, was considered different but more familiar.

Nicolas Cordier’s “Young African” (1607–12), sculpted in part from ancient Roman statue fragments, makes extensive use of black marble. The young man is wearing a tunic completely of the artist’s invention, more Biblical or classical than 17th century. His gestures make sense when we realize that Cordier conceived him to pair with a “Gypsy Girl.” The African is inviting her to dance, but she is turning away in refusal. Both statues, once in Palazzo Borghese, are now in the Louvre, and both should have been in this exhibition instead of just the “Young African,” so visitors could read the underlying hierarchical implication of the duo: though the Gypsy girl — the “Egyptian” — is poor and living by her wits, she still “outranks” the African, who remains outside the European world. Egypt, in the Baroque, had a dual resonance. It was part of ancient Roman history and appeared in history paintings like Pietro da Cortona’s “Caesar Restoring Cleopatra to the Throne” (c. 1637), but also returned to contemporary genre painting with the Romani, always identified as Egyptian. Here we have Simon Vouet’s wonderful “Fortune Teller” (1617), in which a beautiful Gypsy girl is reading the palm of her mark, while an older Romani woman looks at us cheerfully as she picks his pocket. In this genre, the Romani always represent the world as it is, not as it should be, from outside the realm of pious European morality.

Of two models for Bernini’s “Fountain of the Four Rivers” in Piazza Navona on display, one from 1647 shows a personification of the Rio della Plata, the river representing the New World, in the stereotypical guise of Indigenous people of South America, in a crown and skirt of feathers. Conversely, the final version (1649–50) portrays a sub-Saharan African. Bernini frequented the circle of the Jesuit intellectual Athanasius Kircher. Kircher’s colleague Alonso de Ovalle published an account of his missionary work in Chile in which he described its African communities, brought by slavers to work in the mines — hence Bernini’s choice of an African to represent the Americas. In fact, he put a slave band around the leg of the Rio della Plata, though it has been transformed into an ornament and deprived of its telltale iron ring for the chain. Bernini was a keen and acute social observer. Was this a silent condemnation of the slave trade or just reportage? In any case, this sheds new light on the fountain and its development.

The exhibition also demonstrates how religious art cross-pollinated via missionary work by providing the opportunity to compare a 1604–5 engraving by Hieronymus Wierix of “The Death of St. Cecilia” with a dazzling Indian manuscript copy of it from c. 1610. A whole section is dedicated to Baroque depictions of extra-European flora and fauna, often carried by Africans who are clearly enslaved people. We learn the fascinating story of Sitti Ma’ani Gioerida, a Persian woman who in 1617 wed a Roman nobleman, Pietro Della Valle, during his travels. He was no missionary (for once), but a passionate student of Turkish and Persian culture and language, and theirs was a love match, as transpires from his letters to her relatives. She died on their way back to Rome and he embalmed her corpse in honey so she could continue her journey with him. Her burial in the family chapel in Santa Maria in Aracoeli occurred only 10 years later, and here we can see a drawing of her catafalque, an extravaganza of statues and inscriptions describing her virtues in languages including Persian and Syriac.

Another section addresses Roman collections of enticing items from around the world, from a Nauha (Aztec) mask representing Yacatecuhtli (literally, “Lord of the Nose”), god of commerce, to an exquisite alabaster relief portrait of Shah Jahan from 1630–50, probably made by a European artist in India. A series of ecclesiastical vestments decorated with feather “mosaics” from exotic birds in Spanish colonial territories is a breathtaking surprise. The show ends with another embassy: In 1622, the Ottoman Sultan sent the British Ambassador Robert Shirley to Rome with his wife, the Turkish Christian Teresia Sampsonia, to represent the sultan at the papal court. There the couple was painted by the great master of 17th-century portraiture, Anthony van Dyck, in full Persian court dress. They represent the triumphant internationalism of a new age, certainly of war and of European religious expansion, but also of vast and rapid interchanges of art and culture, with Rome at its center. This extraordinary exhibition tells the multifaceted story of how Europe came to see the world outside. It should not be missed.

Global Baroque: The World in Rome in the Age of Bernini continues at the Scuderie del Quirinale (Via Ventiquattro Maggio 16, Rome, Italy) through July 13. The exhibition was organized with Galleria Borghese and curated by Francesca Cappelletti and Francesco Freddolini.