On most golf courses, silence is sacred. At the WM Phoenix Open’s 16th hole, noise is the point.

Every year, tens of thousands of fans pack into a stadium-like enclosure at TPC Scottsdale, turning a short par 3 into one of the most recognizable—and rowdiest—settings in sports. Missed putts are booed. Holes in one trigger cascades of beer. The atmosphere is closer to a college football rivalry than a PGA Tour stop.

But as iconic as the 16th hole has become, its future wasn’t guaranteed by tradition alone. Behind the spectacle, the structure itself had reached a limit—architecturally, operationally, and environmentally.

“We made the decision that that was as good as that structure was going to get,” says Jason Eisenberg, the 2026 tournament chairman. “If we want to continue to have an amazing fan experience, if we want fans to come back and see something new, we were going to have to elevate that experience.”

That realization sparked a full redesign of the 16th hole—one that goes far beyond aesthetics. What’s emerging ahead of the 2026 tournament is a case study in how physical design, systems design, and cultural design can align to quietly change how large-scale events are built and run.

The result isn’t just a louder or flashier venue. It’s a reusable, modular structure designed to last decades, embedded within one of the world’s largest certified zero-waste sporting events—and supported by a culture that treats experimentation as essential, not optional.

TPC Scottsdale is a publicly owned course, operated by the City of Scottsdale and host to the Phoenix Open for decades. Its ownership structure—and the regulatory constraints that come with it—means that even the tournament’s most iconic spaces must be built to appear and disappear each year.

Design Change

Like every structure on the PGA Tour, the 16th hole at the WM Phoenix Open is built from scratch each year and dismantled once the tournament ends. What makes it unusual isn’t that it’s rebuilt annually, but that it has reached the practical limits of how much a temporary structure can evolve without fundamentally changing how it’s designed.

“Every year, we would add to the 16th hole,” says Danny Ellis, senior vice president of sales and business development at InProduction, the company that has built the structure for nearly three decades. “Every year it would take on another section, another layer. Eventually, we reached a point where the footprint couldn’t expand anymore.”

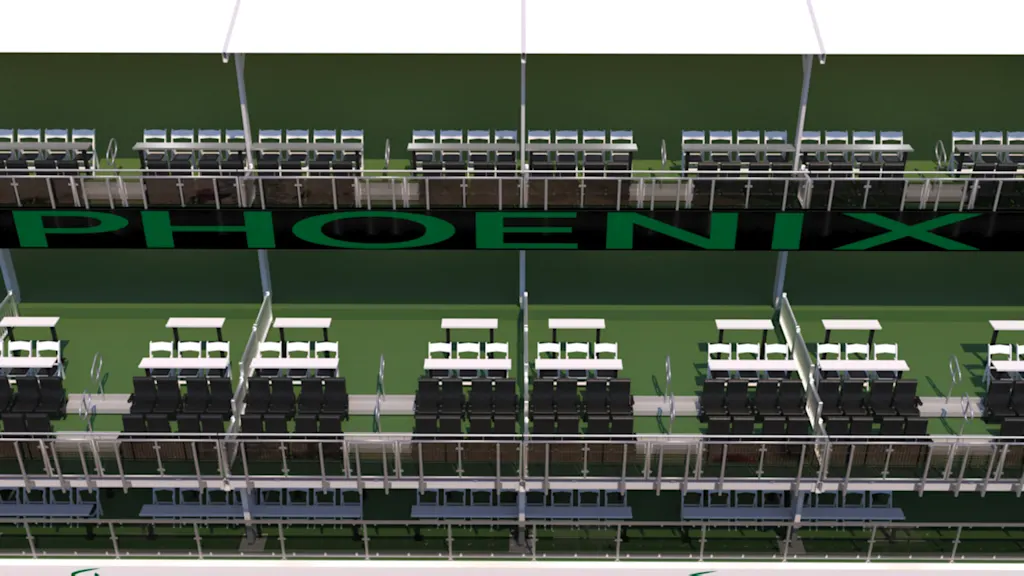

By 2020, the grandstand had reached three levels wrapping fully around the hole. The Thunderbirds, who operate the tournament, were satisfied with its location and scale. What wasn’t sustainable was how it was built. The structure relied heavily on timber and cut plywood, requiring all three levels to be recut, modified, and refinished every year—a process that was increasingly misaligned with both modern fan expectation and the tournament’s zero-waste ambitions.

Across the PGA Tour, temporary construction is the norm. Each week, courses are outfitted with general-admission grandstands, hospitality structures, media centers, broadcast towers, volunteer headquarters, and fan walkways, all designed to exist for a single event. A typical Tour stop might involve roughly 200,000 square feet of temporary flooring spread across an entire course. At most tournaments, those elements are distributed across multiple holes; at the WM Phoenix Open, they are concentrated, layered, and intensified within a single one.

From disposable to reusable

The 16th hole alone doubles that footprint. With approximately 400,000 square feet of flooring contained within a single hole, it operates less like a golf installation and more like a stadium build—rebuilt annually, but engineered for one of the most densely packed fan environments in sports. By both scale and construction method, the 16th hole now occupies a category of its own—without direct analogue on the PGA Tour or at any other sporting event worldwide.

The redesign addresses that mismatch by shifting from disposable construction to modular reuse. Levels two and three have been rebuilt using fully modular decking systems encased in metal frames, eliminating the need for annual cutting on two-thirds of the structure. Only the first level still relies on plywood, reducing construction—related waste at the 16th hole by roughly two-thirds compared to previous builds.

Designing for reuse also changed the structure’s internal logic. Long-span engineering allows for wider interior spaces, fewer vertical supports, and cleaner sight lines—subtle changes that have an outsized impact on how fans move through and experience the space.

“The spans we created inside literally took out every other leg in the structure,” Ellis says. “Before, we had a support every 10 feet. Now, it’s every 20 feet.”

The materials themselves reflect a shift toward permanence without permanence. The structure is built from galvanized steel and aluminum, and incorporates I-beams, bar joists, and glass guardrails—components typically associated with fixed buildings rather than temporary events.

Reducing material use

Dismantling and load-out takes roughly eight weeks, after which the modular components will be stored locally at InProduction’s facility in Goodyear, Arizona. Because much of the structure is custom-sized for the 16th hole, about 20% of the decks and beams will be redeployed to other events, while the remaining components will be reserved for annual assembly. Across InProduction’s broader inventory, those same modular systems will be reused across roughly 300 events each year, allowing materials to circulate continuously rather than being rebuilt from scratch.

For InProduction, aligning with the tournament’s sustainability requirements was a core design constraint. As Ellis explains, the shift to a fully reusable structure was driven in part by a long-running effort to reduce material usage, particularly wood, scrim, and paint that previously had to be recycled, donated, or discarded after each event. From the outset, the goal was to cut construction-related material use. While the cassette flooring system required a higher upfront investment than traditional lumber, Ellis says it delivers long-term savings while eliminating painting and significantly reducing scrim usage, bringing the rebuild into closer alignment with the tournament’s zero-waste strategy.

This is a different interpretation of temporary architecture: one that still appears overnight and disappears just as quickly, but behaves more like infrastructure than spectacle. In doing so, the 16th hole becomes less a one-off anomaly and more a case study in how large-scale events can rethink durability, waste, and experience.

Designing for Experience

The new structure firmly aligns with and reflects the Phoenix Open’s long-standing zero-waste ambitions.

For Tara Hemmer, chief sustainability officer at WM, that significance of the redesign lies less in any single material choice than in how the structure fits into a broader closed-loop system. (Waste Management became the named sponsor of the Phoenix Open in 2010 and rebranded to WM in 2022.)

“Reimagining the construction of the 16th hole and making it modular and completely reusable really speaks to the heart of what it means to be a zero-waste event,” Hemmer says. “This is just another step in that evolution.”

The WM Phoenix Open officially became a zero-waste event in 2013, but Hemmer is quick to point out that it didn’t start with a playbook.

“When we decided to try this, we had no idea how to get to a 100% zero-waste event,” she says. “So we had to try a lot of different things.”

What emerged is a system designed across time, not just space. The process begins months before the tournament, immediately after the previous one ends. The minute the tournament ends, Hemmer and her team are already working on matters for the following year’s tournament.

Aligning with vendors

WM works directly with vendors, specifying which materials can and cannot be used. “We go to them and say, ‘These are the types of materials that you can and can’t use’” Hemmer explains. “Those are selected by the WM team, embedded by the WM team.”

Vendors can propose alternatives, but only if those materials fit into the broader system. “Sometimes we take those and say, ‘That might be a best practice for all of our vendors,’” she says. The goal is simple but demanding: How can each item that comes onto the course be reused, donated, or recycled.

That lifecycle thinking extends into unexpected areas.

“One example I’m really proud of on 16 is beverages,” Hemmer says. “There are a lot of cold beverages, kept cold by ice. Ice melts, and that water has to go somewhere.”

Instead of discharging it, WM designed a reuse loop. “Several years ago, someone came up with the idea: Can we take that water as it’s melting and use it as gray water for our portable toilets?,” said Hemmer. “That’s a great example of design thinking that happens throughout the year.

The WM Green Scene

At the Phoenix Open, there are no trash bins—only compost and recycling. The success of that approach depends as much on psychology as infrastructure.

“We have to make things exciting but also easy,” Hemmer says. “Especially on 16, which tends to be very crowded.”

Signage, bin placement, and staff engagement are carefully designed to reduce contamination. But the ambition goes further. WM spends a lot of time in researching how fans take their messaging home, and apply it.

The WM Green Scene, an interactive fan zone, functions as the tournament’s sustainability classroom. Staffed by WM employee volunteers, the space uses golf-themed games and hands-on demonstrations to teach fans how to identify recyclable and compostable materials. In past years, visitors chipped items resembling cans, bottles, and food waste into the correct bins. This year, the space will also feature a three-dimensional WM Phoenix Open logo that allows fans to recycle bottles and cans directly. Free hydration stations encourage reusable bottles, while the tournament’s 50/50 raffles tie sustainability engagement to charitable giving.

“We’ve learned so much by watching how fans interact,” Hemmer says. “And yes, we’ve also learned how many beverage containers can be consumed in a short period of time.”

Behavior-led system design

“We’ve all seen those cup snakes [collection of stacked cups] going up the 16th hole,” Hemmer says. “That’s important because we need to think through what fans are going to do and how we get those materials back.”

On the 16th hole, behavior is part of the system design. All cold beverages cups used on course are recyclable. WM anticipates misplacement, cup snakes, and even thrown cups, collecting materials from the course and manually sorting every bag to ensure proper processing.

Why Sports Are the Perfect Test Lab

Sporting events offer a rare advantage for experiments such as the modular system: controlled chaos.

“These events are remote,” Ellis says. “They always need infrastructure built temporarily—on a racetrack or a golf course. The level of detail increases every year.”

Hemmer agrees. “The Phoenix Open is a closed event across several hundred acres,” she says. “We can test things at the 16th hole that we test differently at the 12th hole and see what works.”

The stakes are high, but so is the payoff. All of this depends on leadership willing to push past comfort zones.

“The WM Phoenix Open is the WM Phoenix Open because we take chances,” Eisenberg says. “We do things that not just other golf tournaments, but most other events don’t do.”

Nearly a century of community commitment

That confidence comes from trust that has been built over 90 years of community involvement. “We have faith that if we build something and say it’s going to be great, our fans will support us,” he says.

The Thunderbirds’ rotating leadership structure reinforces that mindset. “There is no dictator sitting on the throne for 10 years,” Eisenberg says. “Everybody comes in with fresh ideas, each trying to make it better.”

That culture extends beyond spectacle. Eisenberg points to accessibility improvements and the addition of a family care center as examples of design that’s easy to overlook but deeply intentional.

“I hope they don’t feel any burden getting in and out,” he says of fan accessibility. “I hope it just runs in the background.”

When asked what other tournaments would struggle to replicate, Eisenberg is blunt. “It’s hard to replicate the time we’ve invested,” he says. “We have 90 years of goodwill in our community.” But he also believes the responsibility is clear. “If we can do this at our size and scale, no event has an excuse.”

This weekend, fans will pack into the 16th hole once again. They’ll cheer, boo, and raise their cups skyward. What they likely won’t notice is the modular decks beneath their feet, the materials already destined for reuse, or the systems designed months earlier to make the experience feel effortless. “I hope they walk away thinking it was the most incredible temporary structure they’ve ever been in,” Eisenberg says. “And the best sporting event they’ve ever attended.”