There was a knock on the door. I knew who it was.

Some friends had warned me they might be coming. I had been trying not to think too much about it. I figured I was not high enough on their list. They had already arrested the most outspoken, public-facing government critics — human rights lawyers, opposition politicians, etc. They were already in jail. Why would they come for me?

But they did come for me.

In November 2022, I was arrested in my home country of Nicaragua. I had been a student protester, leading marches and participating in negotiations with the authorities. The government accused me of terrorism and threw me in jail. There, I was psychologically tortured, stripped of my citizenship, and eventually exiled to the U.S.

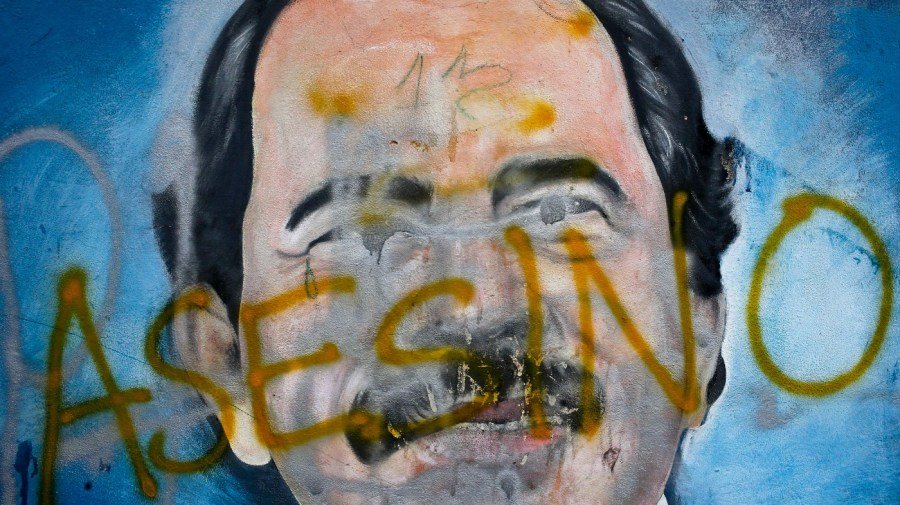

These days, when I read stories of other students — Mahmoud Khalil, Yunseo Chung or Rümeysa Öztürk, for example — my thoughts inevitably turn to my own experience. When I see the protests in Los Angeles met with military force, I am reminded of how President Daniel Ortega responded to our protests. When I hear President Trump accuse protestors of being paid, I remember when Ortega said the same about me.

Throughout my life, I have watched the slow erosion of my own country’s democratic institutions; since my arrival in the U.S., I cannot help but notice the disturbing similarities here.

In Nicaragua, the first step was El Pacto. Ortega, the famous Sandinista comandante of Nicaragua, ruled for 10 years in the 1980s but afterwards lost three subsequent elections. One of the candidates he lost to, the former mayor of Managua, Arnoldo Aleman, was eventually found guilty of stealing as much as $100 million from the impoverished country’s coffers. On the verge of spending 20 years behind bars, he and Ortega, leaders from opposing political parties, struck a series of deals that allowed Ortega to return to power and Aleman to avoid jail time.

Is this so different from New York City’s Democratic mayor, Eric Adams, who, when on the verge of being tried for a what seemed like a slam-dunk corruption case, abruptly reversed course to support Trump’s deportation plans, only to have the Justice Department drop the charges? It’s another El Pacto — just farther north.

A key aspect of Ortega’s consolidation of power has been his war against the Nicaraguan university system. He first restricted their autonomy by forcibly aligning their curricula to the government’s ideologies and placing party loyalists in oversight positions. Not unlike the Trump administration’s revocations of federal funding to universities in the U.S., the University of Central America of Nicaragua, formerly one of the most highly regarded universities in the country, also saw the government cut off its funding.

The Nicaraguan constitution states that 6 percent of the national budget must be distributed to universities. But after Ortega accused the UCA of supporting terrorism because its students participated in the nationwide uprising of 2018, those funds disappeared. At the same time, student protesters across the country saw their scholarships revoked. Ultimately, the UCA and many other universities were seized by the government.

Does this not bear stark similarities to the last few months in the U.S.?

We have seen prestigious U.S. universities accused of terrorism, their federal funding revoked, and the visas of many of their students canceled. The demands made on Harvard called for the university to accept an unprecedented level of government control. Could private universities in the U.S. eventually be seized, just as they have been in Nicaragua?

The University of Central America was an extremely influential Catholic institution, but it was just one of many Catholic organizations that the Nicaraguan government attacked. Despite the fact that Catholicism is an integral part of Nicaraguan national identity, Ortega treats the Church as an opposition entity. He has accused it of money laundering and attacked the Nicaraguan Bishop’s Conference, all while trying to appropriate the faith by promoting clergy who are ideologically in line with his own ends.

Is this not so far off from Vice President Vance’s recent accusations that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops was resettling refugees for financial aims instead of humanitarian ones?

Vance even invoked theological concepts to justify the administration’s immigration policies. New York’s Cardinal Timothy Dolan called the accusations scurrilous; the late Pope Francis publicly contradicted Vance’s theology in a letter to U.S. bishops. In a manner reminiscent of Ortega’s reaction to a papal correction seven years prior, U.S. border czar Tom Homan responded by saying the pope should stick to fixing the Catholic Church.

I must say, when Trump first came onto the political scene, I was attracted to his message: I imagined he would be good for the economy, and he spoke strongly against dictators in Latin America. But now, the dark similarities between leadership in Nicaragua and the U.S. have become undeniable.

I grew up watching democracy in Nicaragua slowly disintegrate, one small step after another. I read of backdoor deals being made, saw universities attacked, and the religious authority of the Catholic Church undermined. When I stood up for democracy, I was accused of terrorism and thrown in jail.

Now here, in the land of the free, I am seeing democracy once again under threat.

How many more knocks on doors will there be?

Miguel Flores is a Nicaraguan political exile, activist and advocate for democracy and human rights.