Mars’s current atmosphere is downright tenuous—conferring less than 1% the pressure of Earth’s—but there’s good evidence that it was substantially thicker in the past. Researchers have now directly observed atoms escaping in a hitherto unobserved way.

That process, known as atmospheric sputtering, may have facilitated Mars’s transition from a watery planet to the arid world it is today, the team reported in Science Advances.

“I’ve been looking for this since I was a postdoc.”

Since the early 2010s, planetary scientist Shannon Curry at the University of Colorado Boulder has pored over data from Mars, looking for signs that the Red Planet’s atmosphere is eroding. It’s been a long journey, she said. “I’ve been looking for this since I was a postdoc.” Colleagues even took to ribbing Curry that her search might be folly. “Every year, I would run my code, and I would look for it,” she said. “We started joking that it was like a unicorn.”

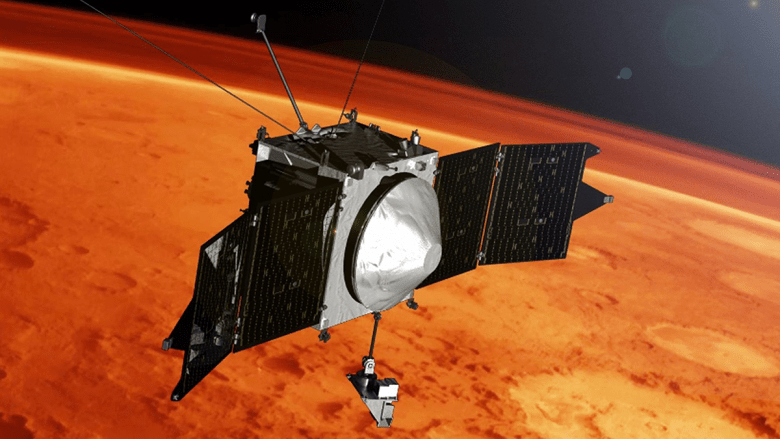

But Curry, the principal investigator of NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission, now has reason to celebrate: She and her colleagues believe they’ve finally captured the first direct observations of sputtering on Mars.

Escaping via Kicks

Planetary atmospheres are constantly changing; everything from solar eclipses to volcanic eruptions to fossil fuel burning can alter their composition, density, and structure. Atmospheres can also erode via several processes. One is photodissociation, in which photons break apart molecules, creating lighter constituents that can go on to escape. Sputtering is another. That process involves high-energy ions, accelerated by the Sun’s electric field, plowing through a planet’s upper atmosphere and colliding with neutral atoms. Those energetic kicks impart enough energy to the neutral particles that they go on to escape the planet’s gravitational field.

Sputtering plays only a minor role in the escape of Mars’s atmosphere today—the rate of sputtering is currently several orders of magnitude lower than that of photodissociation. “But we think, billions of years ago, it was the main driver of escape,” Curry said.

Thanks to nearly a decade’s worth of MAVEN observations, Curry and her collaborators had access to detailed records of the Sun’s electric field and neutral particles in Mars’s atmosphere. They focused on neutral argon, a heavy noble gas. It’s generally difficult to remove argon from the Martian atmosphere in other ways, said Manuel Scherf, an astrophysicist at the Space Research Institute at the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Graz, Austria, who was not involved in the research. “The only really efficient escape mechanism at the moment is sputtering.”

Follow the Darkness

“We have to get out of the sunlight in order to detect sputtering.”

The team used simulations of Mars’s atmosphere to home in on where they might find a signal of sputtering. Looking above an altitude of roughly 360 kilometers seemed to be key, the modeling revealed. The team furthermore knew that it was critical to look at the side of Mars pointing away from the Sun. That’s because photodissociation dominates during the day. “We have to get out of the sunlight in order to detect sputtering,” said Janet Luhmann, a space scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the research team.

The researchers compared the abundances of argon in the Martian atmosphere in two altitude bins: 250–300 and 350–400 kilometers. They also compared periods during which the Sun’s electric field pointed either toward or away from Mars. Sputtering should preferentially occur in the higher-altitude bin when the Sun’s electric field points toward Mars—that’s when ions are accelerated toward the planet’s atmosphere. Indeed, Curry and her colleagues found statistically higher densities of argon in that group of data.

The team calculated that argon was being sputtered at a rate of about 1023 atoms per second. That might seem like a large number, but it’s actually about 100 times lower than the current rate of photodissociation, Luhmann said. But billions of years ago, the Sun’s electric field was likely far stronger than it is today, and sputtering rates could have been much higher, possibly being the dominant contributor to eroding Mars’s atmosphere.

Such a shift could help explain what happened to Mars’s water.

There’s copious evidence that liquid water once existed on the surface of Mars—river valleys, dried lake beds, and other water-carved features persist to this day. This means that Mars’s atmosphere must have once been thick enough to support liquid water. “You need that atmospheric pressure pushing down on water to make it a liquid,” Curry said. But the Red Planet today is an arid world devoid of visible water. Sputtering could explain, at least partially, how the loss of pressure occurred.

And because liquid water is intimately tied to our conception of life, these results have important meaning, Scherf said. “You cannot know whether life can exist somewhere if you don’t understand the atmosphere and how it behaves.”

Curry and her colleagues are hoping to use MAVEN data for years to come, but the team recently learned that they may not have that opportunity: The mission is slated to be canceled in the proposed 2026 federal budget. That’s been a huge blow emotionally, said Curry, but the team isn’t giving up yet. “The United States right now is number one in Mars exploration,” Curry said. “We will lose that if we cancel these assets.”

—Katherine Kornei (@KatherineKornei), Science Writer

Citation: Kornei, K. (2025), Scientists spot sputtering on Mars, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250231. Published on 24 June 2025.

Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.