With more than a decade of experience working as a design and tech analyst, Andrew Hogan is all in on the efficiency and ease that tech brings to our lives. But lately at home with his daughters (ages 4 and 18 months), Hogan is grappling with something unwieldy and undefined: how parents, kids, and technology interact, from smartphones to screen time to AI.

“We are so eager to remove friction—avoid it and smooth over the rough spots, especially as parents,” Hogan says.

In fall 2024, Hogan began writing a newsletter called Parent.Tech, designed to help him, and other parents, better understand how to navigate the increasingly complex world of tech and consumer products. Some of the topics covered include parenting apps, parental controls, AI’s place (or not) in homework, and how to build a framework for kids’ tech use.

“I want to be a better dad, and Parent.Tech was a path to doing that,” Hogan says. “It’s given me some scaffolding and context to make decisions.”

Hogan is parenting children who are on the back end of the “anxious generation,” named for a book written by social psychologist and New York University professor Jonathan Haidt. Touted by Oprah Winfrey and Katie Couric, the book links the steep decline in adolescent mental health to the increased reliance on screens and technology, calling this period in our culture “the great re-wiring of childhood.”

Haidt advocates for more time steeped in unfettered play and fewer hours tethered to tech. While Haidt’s messaging isn’t entirely new (documentaries Screenagers in 2016 and The Social Dilemma in 2020, and the Wait Until 8th campaign have all introduced similar conversations), it’s spurred a renewed interest among parents to seek out new ways to manage tech.

Entrepreneurs are listening. In the past decade, dozens of products have hit the market with the intention of giving kids and their families (everyone, really) the tools to reclaim attention, relationships, and presence.

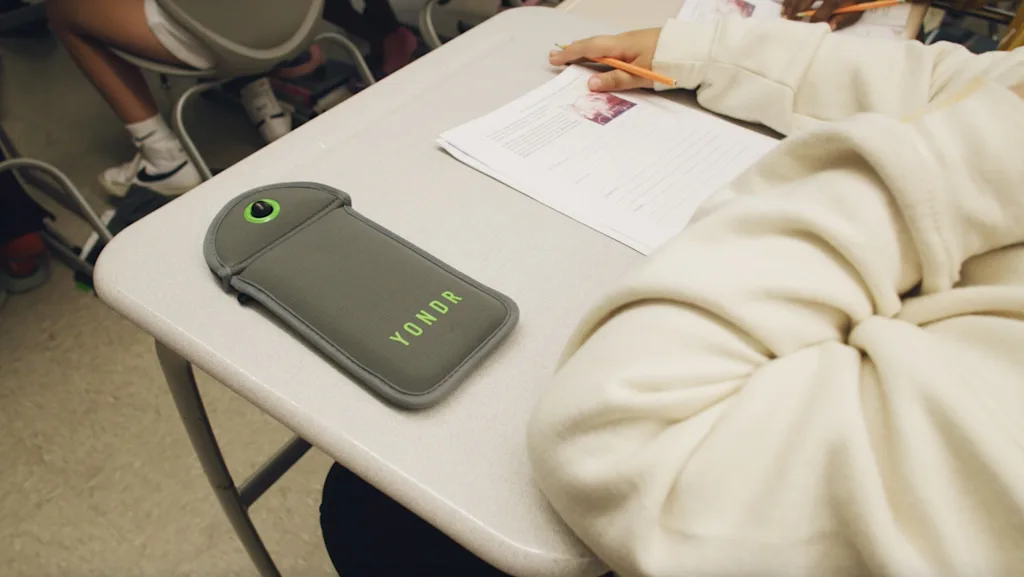

Businesses like Yondr are making it easier for kids to go phone-free in school; startups like Tin Can ($75) are bringing back the landline; and mobile-phone makers including Light Phone ($699), Pinwheel ($119), and Gabb Wireless (phones starting at $149) are offering phones free of social media and web access. Plus, there are untold numbers of toys that promise to help children enjoy the screen-free fun they deserve. These companies have identified a real need—it’s clear by now that willpower alone is not enough to keep humans off their screens. And together they are channeling our techno-anxiety into a new and growing market of products that parents are increasingly willing to shell out for.

Determining the size of this market is still tricky because the products don’t fit into a neat box, despite their shared mission, says Audrey Chee-Read, principal analyst in Forrester’s CMO practice. “What you have isn’t really an established category with specific guardrails [e.g., there’s tech like Gabb that’s considered kids consumer tech versus Yondr that’s not a tech],” she says. “So there is probably a forecast out there on consumer or family tech products [of which Gabb, Tin Can, and Light Phone would be under] but that will also encapsulate other things like gaming.”

Still, it’s clear that these businesses are growing: From 2020 to 2023, Gabb grew 895%, nabbing a spot on the 2024 Inc. 5000 list, while Pinwheel landed in the top 5% of that same list. Jacqueline Nesi, psychologist and assistant professor at Brown University who writes a newsletter called TechnoSapiens and runs a consultancy called Tech Without Stress, says the shift is undeniable: “People realize we can’t get rid of technology so [they’re asking] How do we learn to live with it in a way that promotes our well-being rather than detracts from it?”

Building protected spaces that mimic the “before”

While most children haven’t experienced life without screens, for most parents (especially Gen Xers), there’s a distinct before and after. An increasing number of adults, says Chee-Read, want to tether back to a time when phones weren’t in every pocket and we didn’t feel the pull to check social feeds at school or work. Distraction wasn’t as pervasive in our culture and there was a level of freedom to be in the moment.

For Graham Dugoni, grappling with the desire to spend more time in the “before” made him a founder. His company, Yondr, makes and sells lockable neoprene pouches that allow people to leave their personal tech behind at school, work, concerts, and for other experiences to remove distraction and foster connection. Dugoni refers to the Yondr mission as creating a sort of “National Park system” of protected spaces.

“It’s a big exercise in social psychology,” he says. “What happens in a phone-free space is at some level giving people a sense of freedom that they can’t find in other walks of modern life. We view ourselves as part of a counterculture movement.”

Inspired by philosophers such as Martin Heidegger, who explored what it means to be in the world, and Marshall McLuhan, who studied the effects media has on society, Dugoni started the business in 2014, hand-making the pouches and selling them out of his Toyota RV. Since then, he’s scaled Yondr to reach more than 300% year-over-year growth.

Dugoni hopes his product will become a form of infrastructure for a world with less screen time. The company now works with schools in 35 countries and 50 U.S. states, including one-third of all New York City secondary public schools. Los Angeles Public Schools (80% of middle schools and high schools in the district) work with the company, too, and Yondr’s neoprene pouches are also used at Madison Square Garden and at comedy clubs throughout the U.S.

In fact, one of the first big relationships Dugoni secured was with comedian Dave Chappelle, who asks his audience members to store their phones in Yondr pouches during his shows to protect his act from online leaks and to maintain a distraction-free audience experience. Says Dugoni: “It’s so wildly traditional, it might be revolutionary.”

A big piece of being in any emerging market, he says, is buy-in and consumer education. At schools, that takes the form of writing letters to parents, holding community forums, meeting with school administration, and step-by-step, day-by-day guidance for students and adults on what a phone-free school day looks like.

“We always start with a why,” says David Franklin, Yondr’s manager of partner programming. “We need to change the school culture—that changes attitudes and it pushes this idea forward.”

At concerts and comedy clubs, Yondr employees cruise the line into the venue, talking to attendees about the pouches, how they work, and why they’re a key part of that night’s audience experience. Sometimes, Dugoni says, people resist the idea, wanting to keep their phones available. Other times, folks are happy to try the pouch for a phone-free night.

“The majority of our work is around experience design,” he says. “What things have to be true for this thing to work? It’s about how you approach people and make it conducive to their understanding: ‘This is a special experience and what you are stepping into is worth everyone being there for it.’”

Seizing gaps in the attention economy

Around the same time Dugoni founded Yondr, Kaiwei Tang met his now business partner Joe Hollier at a Google incubator program in 2014. The two founded Light Phone, one of the first “dumbphones” on the market, a year later. The spark for Light Phone was a desire to sidestep the attention economy and a frustration with the available options. Now on its third iteration, Light Phone III (priced at $699) offers people a chance to leave the house with a way to communicate, check the weather, listen to music, or find directions, all while free of the nagging distractions that often come along with smartphones.

And while Tang knew there was a market for his product, he also quickly learned there’d be tension around its adoption. Change can be awkward, and as much as Light Phone built something for people who want some space from always-on tech, there would also be some friction around what using Light Phone means on a granular level.

“We got so much feedback from our users; when people used it, the first 15 or 20 minutes were really nerve-racking,” Tang says. “Everyone had this anxiety. Standing to pay for your groceries and you don’t know what to do. After 15 or 20 minutes, you get over the FOMO, you remember what’s happening, you pay attention to the details of the buildings or trees you never really noticed.”

Managing that dissonance, Tang says, has been a big part of the company’s growth. “Asking anyone to change a longtime behavior is going to be hard,” he admits. “We see it with food. We know we’re eating too much grease. We can’t help ourselves. We’re trying to show the benefits of the organic and healthy food brands, but we’re not asking everyone to become vegan. It’s the same thing with Light Phone. We’re trying to show the benefits of breaking away from the smartphone.”

Gabb Wireless is another business aiming to knock off a sliver of this market, selling Samsung phones dressed in the company’s proprietary software, built specifically for kids and teens. Gabb phones and watches have no internet and no social media. Parental controls are built in, with safety and developmentally appropriate communication tools tailored for kids. Parents also have access to a Gabb app on their phones, allowing them to tap into location sharing, video calls, and text flagging capabilities on their kids’ devices.

CEO Nate Randle says that while businesses in the category started when the conversation around kids and smartphones wasn’t really much of a thing, the market opportunity has been clear from the start. “We talk about TAM [total addressable market],” he says. “There are more than 60 million kids in the U.S. alone between the ages of 5 and 16. There is a wide-open market for an alternative solution to smartphones.”

And for Gabb, showing up as a solution for families and kids has required an awareness around what it means to be a kids’ tech brand. “Traditionally, when someone thinks of a kids’ brand, they go to rainbows and stars,” says Brad Dowdle, VP of creative at Gabb Wireless. “This is Generation Alpha. They’ve grown up around technology. They’re savvy. It has to be aspirational, and they can’t feel we’re designing down to them.”

When business opportunity and cultural change collide

As these solutions emerge and build a following, it’s also important to zoom out on attitudes toward technology, privacy, and life online. For instance, says Chee-Read, while 63% of adults say they’re concerned about online behavior being tracked, less than half of youth report feeling similarly. At the same time, grassroots organizations are pushing for legislation in California, New York, Pennsylvania, and other states to ban phones from school.

A company like Tin Can, which has a mission to make the landline cool again, is showing up on national news and having a viral moment on Instagram. Jerry Chen, the founder of Firewalla, which sells cybersecurity software to homes and businesses to shield everything from baby cameras and laptops to speakers and phones, says in its first five years the business doubled in revenue annually, followed by a “slowdown” of 100% growth every two years. On top of all of this, of course, is a vanishing amount of institutional knowledge and understanding. As technology progresses, the number of people available to provide relevant support and advice on how to manage it—especially as parents—is disappearing.

The factors present five years ago in terms of managing the way technology influences daily life are nearly irrelevant today. And five years from now, we’ll be immersed in entirely new circumstances.

Founders who can manage that kind of market speed and the dissonance around technology and its place in our lives stand to create solutions with real staying power. Entrepreneurs and CEOs like Dugoni, Randle, Tang, and Chen are selling products, yes, but they’re also shaping a new version of what it means to grow up and live in our world. This is not a market built to reject tech but rather to redefine how we relate to it. And for now, Hogan’s hope is that continuing to work on Parent.Tech in his off-hours will help him find the middle path in managing tech tools for himself and his kids. “People need to design these tools, and then we need to pay for these tools,” Hogan says. “We have to figure it out. No one is coming to change it for us.”