On Friday night, the Trump administration deported eight migrants to South Sudan after the Supreme Court — for the second time — gave it permission to go ahead regardless of the Constitution, federal statutory law and international law. In her dissenting opinion from the majority’s first decision in this case, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote that “thousands will suffer violence in far-flung places as a result.”

That time has now come. And the justices in the majority are personally responsible.

Under a federal statute first enacted in 1952, the government can only deport eligible noncitizens to countries from which they arrived or where they want to be removed. If those options are not feasible, Congress specified that the government can consider countries where the deportees are citizens, where they were born or where they have a residence.

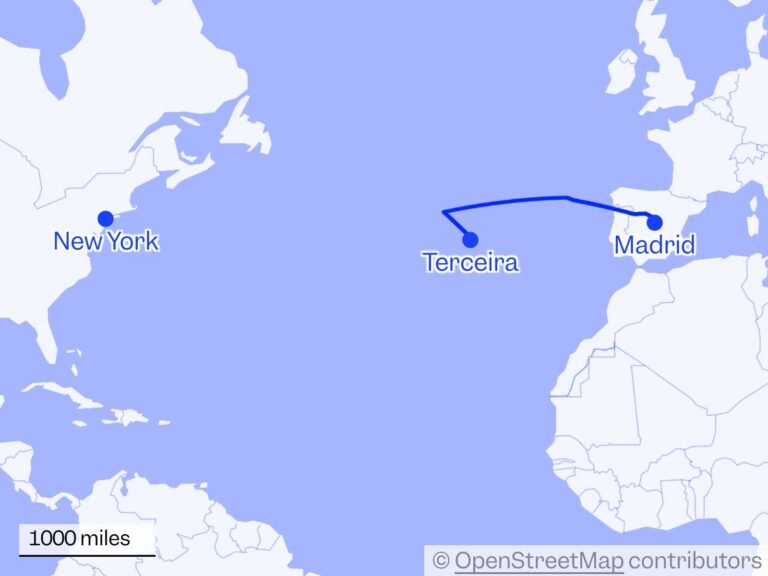

If those don’t work either, the government can consider “third-country removal,” or deportation to any “country with a government that will accept them.” This last route is how more than 200 migrants landed in El Salvador’s notorious CECOT prison, where they still remain. And now eight men are in South Sudan. According to their lawyers, they are originally from Cuba, Laos, Mexico, Myanmar, Vietnam and Sudan (which is separate from South Sudan).

But there’s more. In order to conduct third-country removals, the government must attempt all of the other options first and make a determination that they are all “impracticable, inadvisable, or impossible.”

America is also a party to the 1984 Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which prohibits deporting any person “to another state where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”

In 1988, Congress passed a statute implementing that treaty, which states that the government shall not “expel, extradite, or otherwise effect the involuntary return of any person to a country in which there are substantial grounds for believing the person would be in danger of being subjected to torture, regardless of whether the person is physically present in the United States.”

So before sending a migrant to a third country, the government is supposed to satisfy these legal criteria as well. Normally, a judge assesses whether the government has met its burden. That’s called basic due process.

The Trump administration is snubbing them all.

After a judge ordered that a Guatemalan man could not be removed to his home country, which he had fled after facing torture for being gay, the Trump administration sent him to a third country, Mexico. Then Mexico sent him to Guatemala. The U.S. government didn’t bother to tell the judge that it was even considering a third-country deportation to Mexico, so the man got no due process — the Trump administration just did as it pleased. The administration returned the man to the U.S. in early June after agreeing to comply with a court order, and he was arrested by ICE and moved to an detention facility.

After this incident, a group of noncitizens filed a class action lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security, Secretary Kristi Noem and Attorney General Pam Bondi seeking an injunction preventing their own third-country removals without notice and an opportunity to be heard under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. The lower court judge issued a temporary injunction on March 28, banning third-country removals without due process. The government appealed. On March 31, despite the injunction, the government put more people on a flight to El Salvador even though they had no connection to that country.

On April 18, the lower court issued a second injunction requiring that the government provide noncitizens with notice and an opportunity to be heard in advance of third-country removals. On May 7, the plaintiffs’ lawyers learned that the government was reportedly planning to remove 13 more migrants from Laos, Vietnam and the Philippines to Libya without due process — despite the judge’s orders. A third injunction followed.

Less than two weeks later, it came to light that more third-country deportations, this time to South Sudan, were already en route. The lower court ruled that the government had “unquestionably” violated its order. But instead of directing that the men be returned to the U.S., it allowed the government to hold due process hearings at a military base in the African country of Djibouti.

It was against this backdrop of flagrant violations of the Constitution, federal statutes, an international convention and multiple federal court orders that the far-right majority of the Supreme Court — in a one-paragraph ruling — steamrolled over the lower court and suspended its injunction pending the appeal. No due process hearings, even in Djibouti.

The lower court subsequently issued another order renewing its injunction on the grounds that, however the appeal comes out, the government still can’t just ignore a federal judge’s orders. The Supreme Court majority disagreed, holding that “such a remedy would serve to ‘coerce’ the government into ‘compliance’ and would be unenforceable given our stay of the underlying injunction.”

On Monday, the government of El Salvador stated in a report to the U.N. that, despite its $6 million deal with the Trump administration to house American deportees, “the jurisdiction and legal responsibility for these persons lie exclusively with the competent foreign authorities” such as the U.S.

Kilmar Abrego Garcia — the one person who made it out of CECOT to face criminal charges in the U.S. — reported that while there he was forced to frog-march, kneel from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m., and sustain beatings with boots and wooden batons, threats, hunger, sleep deprivation and psychological torture. If he fell from exhaustion during the kneeling episodes, the guards hit him. He says he lost 31 pounds in two weeks.

Meanwhile, South Sudan is facing a humanitarian crisis, with 7.7 million people — over half its population — “acutely hungry,” according to the U.N. About 1.1 million people have been displaced after nearly five years of conflict between government forces and opposition factions. Health facilities have been forced to shut down, humanitarian workers have been killed and inflation has soared to 180 percent. The worst cholera outbreak in the nation’s history has infected 49,000 people, killing over 900. Last year, severe flooding affected 1.4 million people.

These are the kinds of matters that federal and international law require the Trump administration to consider before sending people to the clutches of a foreign government. The fact that Trump and his posse don’t care was entirely predictable when voters went to the polls on Nov. 5, 2024. The unelected Supreme Court justices have no such excuse.

Kimberly Wehle is author of the book “Pardon Power: How the Pardon System Works — and Why.”