Can AI help neurodivergent adults connect with each other? That’s the bet of a new social network called Synchrony, which believes AI and a well-designed social network with the right safeguards can reduce social atomization and calm the overwhelming cacophony of socializing online.

Launching February 19, the social network debuts during a moment when social media, chatbots, and doomscrolling has made digital communications a hot button topic for parents. “No other app for the neurodiverse is focusing primarily on reducing social anxiety and encouraging friendship,” says cofounder Jamie Pastrano. “I think that’s the biggest piece of it, and no other app is focusing on building an authentic community.”

Synchrony also has support from Starry Foundation and Autism Speaks, two large U.S. advocacy groups, and approval from the Apple App Store.

“I was really blown away about what they’re trying to do,” says Bobby Vossoughi, president of the Starry Foundation. “These kids are isolated and their social cues are off. They’re creating something that could really change this community’s lives for the long term.”

A parenting challenge without a solution

The idea for Synchrony came from Pastrano, a former management consultant and executive sales leader, whose son, Jesse, 21, is autistic. As Jesse experienced teenagerhood, Pastrano became frustrated with the challenges she saw her son facing around the friendship gap; she saw him as a social kid, but planning, timing, even saying the appropriate thing often tripped him up. Unlike other challenges she’d faced as a mother of a neurodivergent child, this one didn’t seem to have a solution.

Research shows that people with autism or neuro developmental differences—roughly 1 in 5 people according to the Neurodiversity Alliance—face increasing loneliness as they transition between adolescence and adulthood. New social responsibilities and expectations for life after school, combined with the loss of support systems that may have been embedded in secondary and university education, can lead to isolation.

One of the cofounders, Brittany Moser, an autism specialist who teaches at Park University in Missouri, says that she’s held crying students who, forced to operate in a world that’s not built for them, are desperate for social connection. She hopes this network can foster it.

“Autism doesn’t end at 18,” Pastrano says. “There was this huge gap in services to support social, emotional, and community needs.”

Pastrano sold her company in 2024 and devoted herself to solving the issue with what would become Synchrony. Part of Pastrano’s inspiration came from reality television. The dating show Love on the Spectrum piqued her interest, causing her to think not about romance, but about connection, friendship, and community. She even contacted a coach on the show, who suggested she get certified at the PEERS program at UCLA, which teaches social and dating skills to young adults on the spectrum.

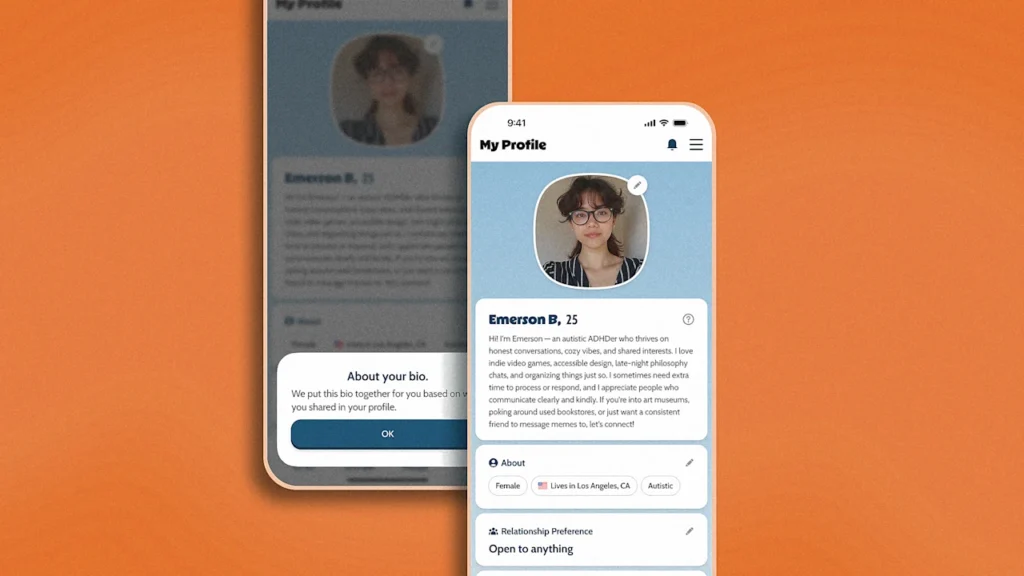

Broadly speaking, Synchrony is built with the same digital infrastructure as a dating site, but is meant for fostering friendships amid a unique population. A big part of the design challenge was making sure it was suitable for the audience, and wasn’t too distracting or loud.

Profiles focus much more on interests, Pastrano says, since interests weigh much more heavily as a reason to communicate among this population. There’s also a space to list neurodiversity classifications and communication style and preferences (“I prefer text to phone calls,” or “I take a few days to reply,” etc.) as part of the effort to front-load key details. Simplified menus and colors and no ads help reduce distractions.

Pastrano also wants to respect the community and focus on healthy experiences and not push for rapid growth; users pay a monthly fee of $44.99 after a free 30-day trial, allowing the network to avoid advertisements. Part of the registration process includes two-step verification—both the user and a trusted person, either a teacher, doctor, or parent needs to input personal details and a photo ID—to make sure bad actors outside the community aren’t given access.

Social Coach, or ‘Seductive Cul-de-sac’

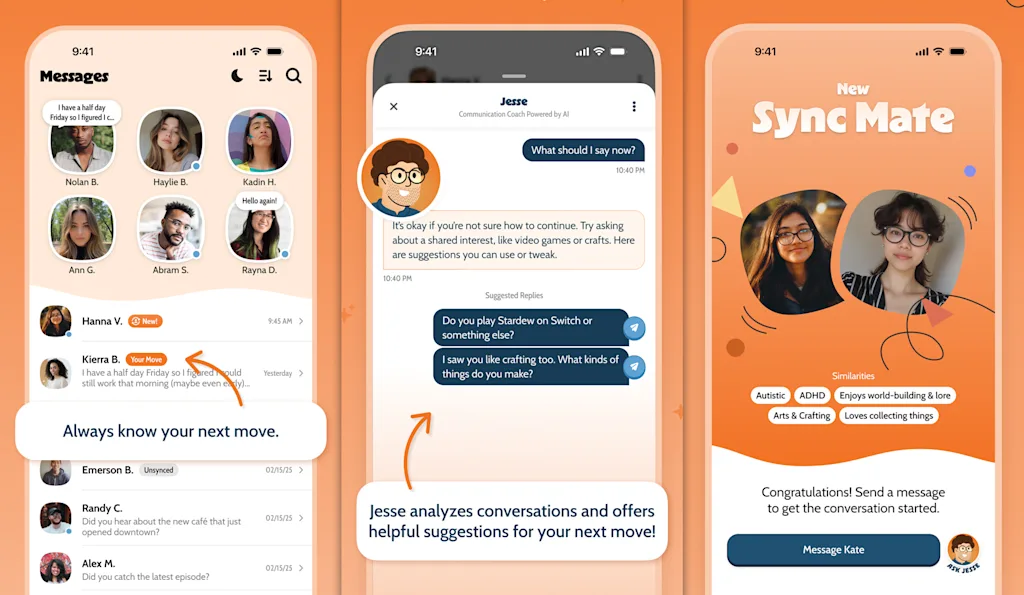

Part of Synchrony’s strategy is the use of Jesse (named after Pastrano’s son), marketed as an “AI-powered social support tool that goes far beyond chat assist technology.” By providing real-time conversation support, the chatbot aims to overcome social anxiety and a lack of confidence around socialization. Talking with Jesse online, developers claim, will bolster user self-assurance and communication skills, eventually manifesting in real life.

When Synchrony users get stuck in an online conversation, they can tap an icon to summon Jesse, who will provide editable solutions to advance or end an interaction. The AI coach offers three main options: a tool to help express yourself, that will offer solutions to continuing the conversation; a button that can help parse through the conversation to help better understand what happened, and whether something might have been meant as flirty or friendly; and a final option to protect, and offer suggestions to set boundaries and exit a conversation quietly.

Built using the Amazon Bedrock large language model and trained by Synchrony staff, Jesse is scanning conversations constantly to provide social coaching when asked.

The use of AI among the neurodivergent population has sparked the same debates as the technology’s use among the population at large. Research by a team at Stanford found that an AI chatbot they developed called Noora, designed to improve communication skills, can improve empathy among users with autism. Some members of the community have claimed AI coaches have helped them with relationships and “transformed” their lives. At the same time, some advocacy groups have warned that chatbot’s emotional manipulation can be more severe for the neurodiverse, and some researchers are concerned AI might reinforce bad communication habits.

British researcher Chris Papadopoulos sums up the state of play in a recent paper, concluding that while “the technology holds the potential to democratize companionship… left unchecked, AI companions could become a seductive cul-de-sac, capturing autistic people in artificial relationships that stunt their growth or even lead them into harm’s way.”

Amid awareness of the sometimes destructive and even deadly consequences of chatbot use, there are significant guardrails built into Jesse, says Moser, including a long list of activities and actions to avoid, like not sharing personal addresses. Jesse is also told not to dispense medical advice. Jesse is not a therapist, and as the founders are clear to note, this isn’t a clinical app.

If users start asking Jesse about off-topic concepts, Moser says it will be programmed to reply something to the effect of, “Hmm, I don’t know if that’s really going to help you connect with the other members.” There will also be warnings if someone is spending too much time just talking with Jesse. Synchrony is launching with human moderation to provide extra safeguards.

Lynn Koegel, a professor and researcher at Stanford University who has studied autism and technology, says her team has spent time updating and changing their models of Noora, to make sure it’s not too harsh, such as not reinforcing communication attempts or being too strict around grammar issues. She says it’s very important to do more in-depth studies and clinical research to make sure these tools do work well and as intended (she has not seen or tested Synchrony).

“My gut feeling is these tools can be very good support,” she says. “The jury is out about whether individual programs that haven’t been tested can be assistive.”

As the Synchrony team works out bugs and final design issues before launch, the challenge becomes building a robust enough community to drive more organic growth. Early user testing that started in December, both an alpha test of 14 users, and closed beta tests among university support groups for autistic students, helped them refine the model and layout.

The marketing strategy at launch doesn’t focus on the users themselves, but rather neurodiverse employer groups, universities that have neurodiverse programs (who can create their own closed-loop, campus versions of the app), advocates, and relevant podcast hosts.

“Success is about awareness and attention,” says Pastrano. “It’s not a numbers game for me. It’s a really personal game.”