In “Uh, As If!” (2014), a two-minute video work by Young Joon Kwak, a flick of the artist’s wrist turns from “a ubiquitous signifier of queer identity and femininity,” as their curatorial text notes, to “a tactic for resisting domination over one’s body.” I also found it frankly meditative. Each flick of the wrist splatters paint off camera, and their hand, covered in gray paint and neon pink nail polish, begins to look like a shadow puppet coming to life.

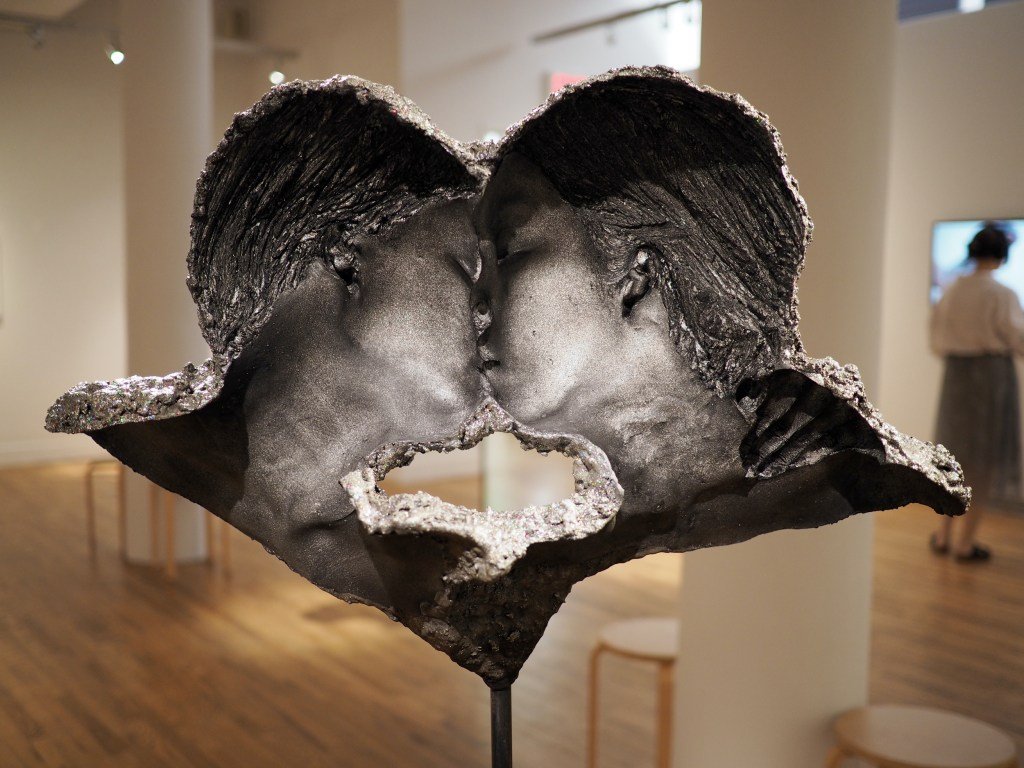

Shadow and light exist outside a binary in RESISTERHOOD, Kwak’s current exhibition at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art. The artist’s magnificent sculptures tell multiple stories that look at contemporary queer and trans existence. Take, for example, “Femmmes (Nic, Toria, Yara)” (2025) — and yes, that’s three m’s — a seemingly abstract form crafted from dark resin. Kwak made the shape by pouring liquid silicone and plaster on three nonbinary individuals embracing each other and then refining it further in their studio. The resin faces outward, while 10,000 rhinestones face the wall. Though the rhinestones are hidden from the viewer, spotlights on the sculpture create a halo of glittering light surrounding it. The splendor of this community of individuals is not immediate or obvious, but it’s glorious nonetheless.

In “To Refuse Looking Away from Our Transitioning Bodies (Me and My Fat *****)” (2023), a cast of Kwak’s friend’s torso glitters with rainbow rhinestones alongside the equally luminescent “To See Your Self Reflected in Our Chameleonic Transformations (Drag Ban)” (2023), a painting that serves as a metaphor for both standing in the spotlight and hiding within. The chameleon — a creature that transforms appearance at will — is a reminder of the mutability of our terrestrial bodies.

But part of what gives “To Refuse” its charm is the reverse — unlike “Femmmes,” Kwak has hung this work so we can see both sides of it. If one side dazzles, the other shows us all the details of their model’s body, including outlines of a corset and folds of skin. That mold is also the foundation for “My Fat ***** (II)” (2024), a monoprint of the same figure.

The permanence of these works contrasts with the realities of the transitioning body that Kwak has cast, which, as the exhibition text notes, exists in “states of emergence and indeterminacy.” Which is true, I’d add, for any body, but some of us come to this understanding of the impermanence of corporeal life much sooner than others.

In Kwak’s “Glitter Mani Festo,” a zine composed of 30 statements whose PDF (sans glitter) is available online, we learn that our draw toward shiny things comes from an instinct to seek out water, which shimmers in sunlight. Shiny objects like mica, pyrite, and other gems eventually became associated with royalty. And then along came the paradox of glitter: “a material of luxury and kitsch, simultaneously devalued and beloved.”

Circulating the room, I loved how each sculpture, drawing, and print opened up new perspectives based on the angle and light. As item 19 in Kwak’s manifesto states, “Glitter has an indeterminate relation to color — reflecting and refracting any color of the spectrum in its environment.” That made these works tricky to photograph, but all the more enjoyable because they resist a single point of view. The artworks themselves remind me of glitter, and of trans and nonbinary existence — and, to be honest, of the universe itself.

Young Joon Kwak: RESISTERHOOD continues at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art (26 Wooster Street, Soho, Manhattan) through July 27. The show was curated by Stamatina Gregory.